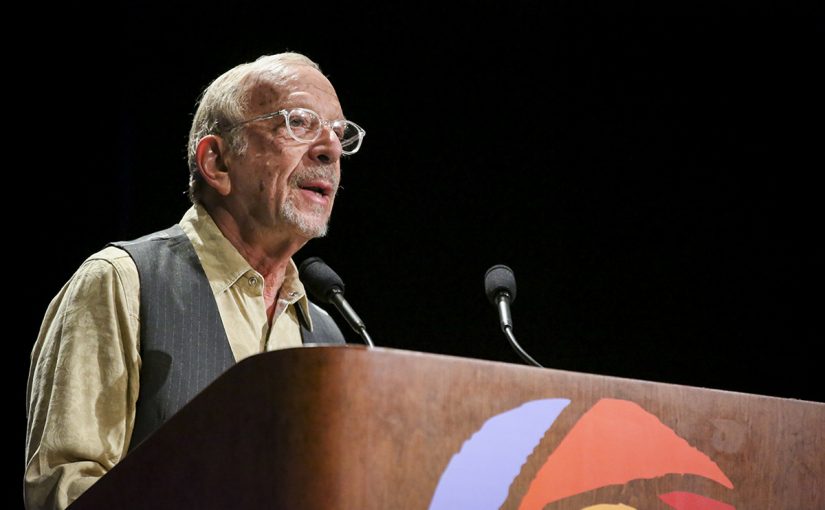

While society prepares for the future of a world ravaged by climate change, environmental educator David Orr has spent years writing about how to reverse it. Orr advocates for an ecological design revolution to change how we build homes, grow food and model society, so that future generations can thrive. We can build a more resilient world by simply asking ourselves: “How would nature do it?”

In his book, Hope Is an Imperative: The Essential David Orr, Orr frames our devotion to fossil fuels as a moral lapse best judged from the perspective of our descendants. Young people are set to bear the brunt of these climate consequences, so to put power back in their hands, we must engage them in building a more sustainable world.

Orr will present a keynote address at the 2019 Bioneers Conference. Buy your tickets to Bioneers 2019 here.

Following is an excerpt from Hope Is an Imperative: The Essential David Orr.

To see our situation more clearly, we need a perspective that transcends the minutiae of science, economics, and current politics. Since the effects, whatever they may be, will fall most heavily on future generations, understanding their likely perspective on our present decisions would be useful to us now. And how are future generations likely to regard various positions in the debate about climatic change? Will they applaud the precision of our economic calculations that discounted their prospects to the vanishing point? Will they think us prudent for delaying action until the last-minute scientific doubts were quenched? Will they admire our heroic devotion to inefficient cars and sport utility vehicles, urban sprawl, and consumption? Hardly. They are more likely, I think, to judge us much as we now judge the parties in the debate on slavery prior to the Civil War.

Stripped to its essentials, defenders of the idea that humans can hold other humans in bondage developed four lines of argument. First, citing Greek and Roman civilization, some justified slavery by arguing that the advance of human culture and freedom had always depended on slavery. “It was an inevitable law of society,” according to John C. Calhoun, “that one portion of the community depended upon the labor of another portion over which it must unavoidably exercise control” (Miller, W. L., 1998, 132). And “freedom,” the editor of the Richmond Inquirer once declared, “is not possible without slavery” (Oakes 1998, 141). This line of thought, discordant when appraised against other self-evident doctrines that “all men are created equal,” is a tribute to the capacity of the human mind to simultaneously accommodate antithetical principles. Nonetheless, it was used by some of the most ardent defenders of “freedom” right up to the Civil War.

A second line of argument was that slaves were really better off living here in servitude than they would have been in Africa. Slaves, according to Calhoun, “had never existed in so comfortable, so respectable, or so civilized a condition as that which [they] enjoyed in the Southern States” (Miller, W. L., 1998, 132). The “happy slave” argument fared badly with the brute facts of slavery that became vivid for the American public only when dramatized by Harriet Beecher Stowe in Uncle Tom’s Cabin published in 1852.

A third argument for slavery was cast in cost-benefit terms. The South, it was said, could not afford to free its slaves without causing widespread economic and financial ruin. This argument put none too fine a point on the issue; slavery was simply a matter of economic survival for the ruling race.

A fourth argument, developed most forcefully by Calhoun, held that slavery, whatever its liabilities, was up to the various states, and the federal government had no right to interfere with it because the Constitution was a compact between independent political units. Beneath all such arguments, of course, lay bedrock contempt for human equality, dignity, and freedom. Most of us, in a more enlightened age, find such views repugnant.

While the parallels are not exact between arguments for slavery and those used to justify inaction in the face of prospective climatic change, they are, perhaps, sufficiently close to be instructive. First, those saying that we do not know enough yet to limit our emission of greenhouse gases argue that human civilization, by which they mean mostly economic growth for the already wealthy, depends on the consumption of fossil fuels. We, in other words, must take substantial risks with our children’s future for a purportedly higher cause: the material progress of civilization now dependent on the combustion of fossil fuels. Doing so, it is argued, will add to the stock of human wealth that will enable subsequent generations to better cope with the messes that we will leave behind.

Second, proponents of procrastination now frequently admit the possibility of climatic change but argue that it will lead to a better world. Carbon enrichment of the atmosphere will speed plant growth, enabling agriculture to flourish, increasing yields, lowering food prices, and so forth. Further, while some parts of the world may suffer, a warmer world will, on balance, be a nicer and more productive place for succeeding generations.

Third, some, arguing from a cost-benefit perspective, assert that energy conservation and solar energy are simply too expensive now. We must wait for technological breakthroughs to reduce the cost of energy efficiency and a solar-powered world. Meanwhile we continue to expand our dependence on fossil fuels, thereby making any subsequent transition still more expensive and difficult.

Finally, arguments for procrastination are grounded in a modern-day version of states’ rights and extreme libertarianism, which makes squandering fossil fuels a matter of individual rights, devil take the hindmost.

The fit between slavery and our present use of fossil fuels is by no means perfect, but it is close enough to be suggestive. Of course we do not intend to enslave subsequent generations, but we will leave them in bondage to degraded climatic and ecological conditions that we will have created. Further, they will know that we failed to act on their behalf with alacrity even after it became clear that our failure to use energy efficiently and develop alternative sources of energy would severely damage their prospects. In fact, I am inclined to think that our dereliction will be judged as a more egregious moral lapse than that which we now attribute to slave owners. For reasons that one day will be regarded as no more substantial than those supporting slavery, we knowingly bequeathed the risks and results of climatic change to all subsequent generations, everywhere.

If not checked soon, that legacy will include severe droughts, heat waves, famine, changing disease patterns, rising sea levels, and political and economic instability. It will also mean degraded political, economic, and social institutions burdened by bitter conflicts over declining supplies of fossil fuels, water, and food. It is not far-fetched to think that human institutions, including democratic governments, will break under such conditions.

Other similarities exist. Both the use of humans as slaves and the use of fossil fuels allow those in control to command more work than would otherwise be possible. Both inflate wealth of some by robbing others. Both systems work only so long as something is underpriced: the devalued lives and labor of a bondsman or fossil fuels priced below their replacement costs. Both require that some costs be ignored: those to human beings stripped of choice, dignity, and freedom or the cost of environmental “externalities,” which cast a long shadow on the prospects of our descendants. In the case of slavery, the effects were egregious, brutal, and immediate. But massive use of fossil fuels simply defers the costs, different but no less burdensome, onto our descendants, who will suffer the consequences with no prospect of manumission. Slavery warped the politics and cultural evolution of the South. But our dependence on fossil fuels has also warped and corrupted our politics and culture in ways too numerous to count. Slaves could be manumitted, but the growing numbers of victims of global warming have no reprieve. We leave behind steadily worsening conditions that cannot be altered in any time span meaningful to humans.

Both slavery and fossil fuel–powered industrial societies require a mass denial of responsibility. Slave owners were caught in a moral quandary. Their predicament, in James Oakes’s words, was “the product of a deeply rooted psychological ambivalence that impels the individual to behave in ways that violate fundamental norms even as they fulfill basic desires” (Oakes 1998, 120). Regarding slavery, George Washington confessed, “I shall frankly declare to you that I do not like even to think, much less talk, of it.” As one Louisiana slave owner put it, “a gloomy cloud is hanging over our whole land.” Many wished for some way out of a profoundly troubling reality. Instead of finding a decent way out, however, the South created a culture of denial around the institutions of bondage. They were enslaved by their own system until it came crashing down around them in the Civil War.

We, too, find ourselves in a quandary. A poll conducted for the American Geophysical Union revealed that most Americans believe that global warming is real and that its consequences will be tragic and irreversible. But the response of Congress and much of the business community has been to deny that the problem exists and continue with business as usual. Proposals for higher gasoline taxes, increasing fuel efficiency, or limits on use of automobiles, for example, are regarded as politically impossible as the abolition of slavery in the 1830s. Unless we take appropriate steps soon, our system, too, will end badly.

We now know that heated arguments made for the enslavement of human beings were both morally wrong and self-defeating. The more alert knew this early on. Benjamin Franklin noted that slaves “pejorate the families that use them; the white children become proud, disgusted with labor, and being educated in idleness, are rendered unfit to get a living by industry” (Finley 1980, 100). Thomas Jefferson knew all too well that slavery degraded slaves and slave owners alike, while providing no sustainable basis for prosperity in an emerging capitalist economy. In a rough parallel, it is possible that the extravagant use of fossil fuels has become a substitute for intelligence, exertion, design skill, and foresight. On the other hand, we have every reason to believe that vastly improved energy efficiency and an expeditious transition to a solar-powered society would be to our advantage, morally and economically. Energy efficiency could lower our energy bill in the U.S. alone by as much as $200 billion per year (Hawken et al. 1999). It would reduce environmental impacts associated with mining, processing, transportation, and combustion of fossil fuels and promote better technology. Elimination of subsidies for fossil fuels, nuclear power, and automobiles would save tens of billions each year (Myers 1998). In other words, the “no regrets” steps necessary to avert the possibility of severe climatic change, taken for sound ethical reasons, are the same steps we ought to take for reasons of economic self-interest. History rarely offers such a clear convergence of ethics and self-interest.

If we are to take this opportunity, however, we must be clear that the issue of climatic change is not, first and foremost, a matter of economics, technology, or science but, rather, a matter of principle that is best seen from the vantage point of our descendants. The same historical period that gave us slavery also gave us the principles necessary to abolish it. What Thomas Jefferson called “remote tyranny” was not merely tyranny remote in space but in time as well—what Bill McDonough has termed “intergenerational remote tyranny.” In a letter to James Madison written in 1789, Jefferson argued that no generation had the right to impose debt on its descendants, for were it to do so, the future would be ruled by the dead, not the living.

A similar principle applies in this instance. Drawing from Jefferson, Aldo Leopold, and others, such a principle might be stated thusly:

No person, institution, or nation has the right to participate in activities that contribute to large-scale, irreversible changes of the Earth’s biogeochemical cycles or undermine the integrity, stability, and beauty of the Earth’s ecologies—the consequences of which would fall on succeeding generations as an irrevocable form of remote tyranny.

That principle will likely fall on uncomprehending ears in Congress and in most corporate boardrooms. Who, then, will act on it? Who ought to act? Who can lead? What institutions represent the interests of our children and succeeding generations on whom the cost of present inaction will fall? At the top of my list are those that purport to educate and thereby to equip the young for useful and decent lives. Education is done in many ways, the most powerful of which is by example. The example the present generation needs most from those who propose to prepare them for responsible adulthood is a clear signal that their teachers and mentors are themselves responsible and will not, for any reason, encumber their future with risk or debt—ecological or economic. And they need to know that our commitment is more than just talk. This principle can be stated in these words:

The institutions that purport to induct the young into responsible adulthood ought themselves to operate responsibly, which is to say that they should not act in ways that might plausibly undermine the world their students will inherit.

Accordingly, I propose that every school, college, and university stand up and be counted on the issue of climatic change by beginning now to develop plans to reduce and eventually eliminate or offset the emission of heat-trapping gases by the year 2020. Opposition to such a proposal will, predictably, follow along three lines. The first line of objection will arise from those who argue that we do not yet know enough to act. In other words, until the threat of climatic change is clear beyond any possible doubt (and also less easily reversed), we cannot act. Presumably, these same people do not wait until they smell smoke in the house at 2 am to purchase fire insurance. A “no regrets” strategy relative to the far-from remote possibility of climatic change is, by the same logic, a way to insure our descendants against the possibility of disaster otherwise caused by our carelessness.

A second line of objection will come from those who will argue that even so, educational institutions on their own cannot afford to act. To be certain, there will be initial expenses, but there are also quick savings from reducing energy use. In fact, done smartly, implementation of energy efficiency and solar technology can save money. Moreover, it is now possible to use energy service companies that will finance the work and pay themselves from the stream of savings, making the transition budget neutral. The real problem here has less to do with costs than with moral energy and the failure to imagine possibilities in places where imagination and creativity are reportedly much valued.

A third kind of objection will come from those who agree with the overall goal of stabilizing climate but will argue that our business is education, not social change. This position is premised on the quaint belief that what occurs in educational institutions must be uncontaminated by contact with the affairs of the world and that we have no business objecting to how that world does its business. It is further assumed that education occurs only in classrooms and must be remote from anything having practical consequences. Were the effort to eliminate the use of fossil fuels, however, done as a 20-year effort in which students worked with faculty, staff, administration, energy engineers, and technical experts, the educational and institutional benefits would be substantial.

How might the abolition of fossil fuels occur? In outline, the basic steps are straightforward, requiring:

- thorough audit of current institutional energy use;

- preparation of detailed engineering plans to upgrade energy efficiency and eliminate waste;

- development of plans to harness renewable energy sources sufficient to meet campus energy needs by 2020;

- competent implementation.

These steps ought to engage students, faculty, administration, staff, and representatives of the surrounding community. They ought to be taken publicly as a way to educate a broad constituency about the consequences of our present course and the possibilities and opportunities for change.

The longer-term goal of this effort is to begin, from the grassroots, the long-delayed transition to energy efficiency and solar power. Perhaps our leaders will follow one day when they are wise enough to distinguish the public interest from narrow short-run private interests. Someday, too, all of us will come to understand that true prosperity neither permits nor requires bondage of any human being, in any form, for any reason, now or ever.

From Hope Is an Imperative: The Essential David Orr by David W. Orr. Copyright © 2011 Island Press.