Mariel Nanasi is a renowned civil rights and criminal defense attorney, as well as a zealous social organizer. She is the executive director and president of the New Mexico-based nonprofit, New Energy Economy, which works to protect communities from the social, economic, health, and environmental costs of extractive energy and usher in an affordable, clean, sustainable energy future.

We at Bioneers were truly honored to have Mariel Nanasi speak at the 2017 conference. Below is a video and excerpted transcript of her keynote on the significant shift toward a clean energy economy.

Mariel Nanasi:

It’s truly an honor to be here in this critical time, building the strength of our movement. I’m excited to share with you all my story and the important lessons we’ve learned in New Mexico about what it’s going to take to shift from an energy colony to an energy democracy for our state and for our nation. But first, I need to honor the vehicle of my work, the organization and team of New Energy Economy. I’d like to share a video made by my dear colleague, we call her the communications specialist at New Energy Economy, Lyla June Johnston.

As the video illustrates, we’re doing really exciting work in New Mexico, and it’s kind of crazy to find myself in the middle of it. I’ve been a civil rights lawyer for 15 years, and I worked as an attorney representing victims of police and guard violence and abuse, including death, in Chicago and New Mexico. I have no science background. I have no energy background. Up until eight years ago, if you asked me what the impact of me turning on a light was, flicking the switch, where does our electricity come from, I honestly would not have been able to tell you.

Then eight years ago I was sitting somewhere out there, in this audience, and I found myself called to a new task. It was my first Bioneers conference.

I knew about climate change but hadn’t appreciated the urgency of it. When I turned my attention and my heart to actually face it, the enormity and severity of it, I knew I had to shift my work. I thought, how can I look at my children in their eyes and know about climate change and didn’t use my talents to address it. So I decided right there, eight years ago, that I needed to shift my work, to do my part to create bold solutions to the climate challenge. And I remember thinking, that I would like to do something worthy of standing on this stage before you. And now I’m here.

It’s been a long and arduous journey, and I’ve learned a lot about naivety, corruption and courage along the way. After my Bioneers experience, I went home like each one of you will. I had a new fire burning inside me. I asked around to learn who was doing the best work in Sante Fe, and people repeatedly told me New Energy Economy. So I met with the executive director and I asked to volunteer, which I did, and three months later I asked for a job. My then boss said, I can’t pay you a lawyer salary. And I said, Just pay me what you can; I want to work with you. Note to all the young people in the audience: Volunteer and make them fall in love with you, and work your butt off, and then you can learn and make change.

I worked at New Energy Economy as a senior policy advisor. It was 2008. I learned that burning coal is the single greatest source of carbon emissions. I learned that New Mexico produces 60 percent of our energy from coal. Solar at that point just made up a mere 1 percent. I thought that perhaps the decision makers just haven’t realized the magnitude of the climate crisis. I thought, in beautiful sunny New Mexico surely we should promptly close coal and replace that energy with energy from solar and wind, of which there is an abundance in New Mexico. We even have the sun Zia on our flag.

So fast forward. The founder of New Energy Economy asked me to take over as executive director. In an enormous moment of opportunity I found myself at the table negotiating with PNM about how they were going to comply with an EPA ruling that found that their coal plant—the San Juan coal plant in the northwest part of our state in Diné country, one of the oldest and dirtiest plants in the country—needed to clean up its act. At the time the plant had 60,000 air quality violations—60,000. The ruling fell under the regional Hayes Act.

The illegal issue with the plant was not its 11 million tons of carbon pollution every year, or the $60 million in externalized healthcare costs associated with cancer and respiratory illness, lung disease and heart disease it caused, but visibility. It was impeding the view in national parks across the West, including the Grand Canyon.

We fought hard to get a seat at the negotiating table. While there we articulated an idea that I ended up literally speaking the resolution of the puzzle: how to address this demand from the federal government in a way that would cause the least economic harm. PNM and the other owners should close two units of the coal plant by the end of this year rather than install pollution controls that would extend the life of the plant. It was a huge victory.

But then, PNM announced that it was going to settle with EPA and it wouldn’t settle with us. The table was filled with all male lawyers, executives and officials. I was the only woman in the room. They announced that they were going to close half the coal plant, as we had proposed, but instead of replacing the lost energy with solar and wind, as we were demanding, they were going to purchase more coal from the remaining units being abandoned by California owners, and expand their nuclear investment in Palo Verde nuclear plant in Arizona. I turned to PNM’s senior vice president, raised my voice, tears fell from my eyes, and I literally said, “What about the children!”

____

Many of you know what it is like when someone close to you dies and you are so filled with grief that it’s hard to understand how the world is continuing. Everything looked sort of foggy and the sadness is overwhelming, and that’s how I felt that day, and I was just sort of walking.

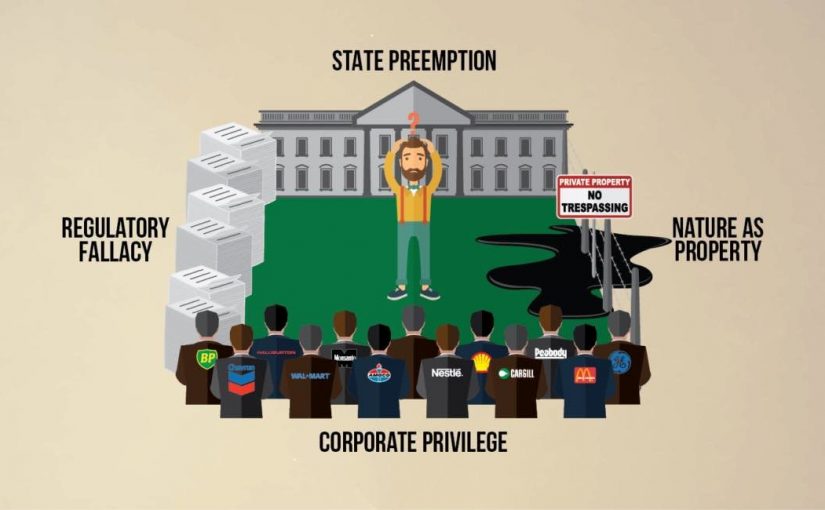

The next day I came back, a sense of determination to never allow this dismissal to ever happen again. I learned something very profound from that experience, that the investor-owned utilities can accommodate environmentalists as long as we don’t actually challenge their fundamental business model.

PNM was willing to acknowledge and even afford time for our concerns, as long as it was contained within their framework. I began to more fully understand that there is a hierarchy that privileges and profits a few at the expense of many and in this equation, there are serious vested interests in maintaining things as they are. In fact, this entrenched power dynamic, in the case of energy, is perhaps the most extreme example, as fossil fuel companies are the wealthiest corporations on the planet. Energy corporations have more money than in the history of money. And energy is the foundation of our economy. In our current time, the basis of that foundation is extraction.

The economic underpinnings of the extractive economy, including the extreme emphasis on the privatization and accumulation of wealth, devastating exploitation of the land, water and air, and as Kandi Mossett said, sacrificing the people who live in close proximity to the power plant, and income, labor and power disparities. Extraction is the business model.

These are not unmanned endeavors. The project of extraction, when it comes to New Mexico and the vast majority of states in the US, is carried out by regulated monopolies—the investor-owned utilities or IOUs—who have been given power and permission to prioritize profit in their delivery of fundamental public good. These corporations have assumed state-like powers in ruling over workers, communities, and democracy itself. They have a deeply vested interest in both protecting their monopoly as well as the investments that they’ve made in giant coal and nuclear plants.

The painful lesson I learned from my naiveté during the PNM/EPA negotiation was that unless one wields power, or unless we wield power, the corporation will always default to its fiduciary obligation—dividends for shareholders, short-term earnings growth, and bonuses for senior management. My pleas for the children or persuasive arguments to address climate change made little difference. We were not going to be able to get anywhere from asking.

Frederick Douglass said, “Power concedes nothing without a demand.” We needed to demand, and we needed a movement to deliver that demand and hold the corporations accountable, for another thing about the energy system is that the regulators that are elected or appointed, supposedly to ensure a balancing of the private/profit motive with the public interest, are wined and dined, literally, by the very entities that they are meant to regulate.

As PNM doubled down on coal and nuclear, we doubled down on our movement-building work. Organizing is the hardest work, but also the most meaningful work. It’s about the fundamental task of engaging people, building mutually beneficial relationships and a shared vision and path to justice. So we organized. We fight in the courts. We ousted corrupt regulators. We translated this seemingly arcane energy case into the language of the people, so our people could recognize what’s at stake.

And I want to talk to you about what’s at stake.

We are at a crossroads. We either face the very real possibility of a planet on hospice, driven by an energy system that is the epitome of capitalism on steroids with extreme exploitation and racism at its core. Or a profound opportunity to shift at the very basis of our economic system that we haven’t seen since the abolition of slavery. And it’s really up to us which way we go.

Naomi Klein, a heroine of mine, has a quote in the beginning of her book, The Shock Doctrine, from Milton Friedman, about the need to have policies on the shelf to take advantage of and deploy in times of crisis. What are the policies sitting ready on our movement’s shelf? What are our ready-made demands standing by for that time in which the balance of power shifts and there’s an opening? We have been building towards this moment of destabilization. Now what? Eighty-nine percent of the people across race and class support more renewable energy. But is that enough? Do we just stop there?

I want to caution us in this critical time to not simply bank on a technological fix. To seize a much more profound opportunity than switching a corporate, monopoly-controlled, fossil fuel energy economy for a corporate, monopoly-controlled solar economy. Too often calls for a transition to carbon-free energy do not specify who will develop and control that energy, to what end, or to whose benefit. They emphasize a transition to industrial scale, carbon-free energy resources without challenging the growth of energy consumption, material consumption, rates of capital accumulation, and concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a few.

In this model, and we hear it often today, nuclear energy is being embraced as a carbon-free energy source. Even while it is now the most expensive form of energy on the market, is tied to the devastation of native lands and communities from uranium mining, and presents an unsolvable problem of waste in a mature industry of 50 years, not to mention an inordinate amount of precious water. It’s time to create energy democracy.

Energy democracy demands that renewable energy resources are used to enable a new alternative economy, a regenerative rather than extractive economy, a critical framework for addressing the economic and racial inequities that a decarbonized economic system would otherwise continue to perpetuate. It seeks to reframe energy from being a commodity that is commercially exploited to being a part of our commons, a natural resource to serve human needs but in a way that respects the Earth and the ecosystem services provided by the biosphere. As a communal resource it requires democratic ownership structures and sustainable ecological management.

The new paradigm calls for reducing the human footprint, reducing waste, and reducing energy use as a key to the ecosystem health and stewardship. How we build matters. Renewable energy needs to foster community-based development, non-exploitive forms of production, socialized capital, ecological use of natural resources, and sustainable economic relationships.

At the heart of this movement are decentralized energy projects to improve the health, local economy, and resilience of low-income communities and communities of color. And you can see in the video, linked above, that we’ve been doing that, anchoring solar energy projects in our community. The vision and movement for fundamentally different energy system and society rocks the status quo, upsetting a legacy of entrenched power, privilege, property and profits. It’s going to be harder, but it’s going to be beautiful and worth the fight. Nelson Mandela says, “Courage is not the absence of fear but the triumph over it.” It’s feeling the fear and walking through it.

Just like I was sitting there eight years ago, this movement needs your talents, your chutzpah, and your work.

____

I want to end by sharing this story of Camiam Woody. I took this picture of Camiam Woody, a 5-year-old native child who lives in Farmington just miles from the San Juan coal plant. He needs a pump to breathe. We placed this billboard at the most trafficked intersection in Albuquerque. I keep him in mind and in heart, whether I’m arguing in a court or speaking in a classroom or at a demonstration.

Activism is the antidote to despair. Join us in this fight to decolonize our minds, open our hearts, take care of each other, and stop this fossil fuel war against this people and Mother Earth.

Sol, not coal!