Shannon Dosemagen is a Co-Founder and Executive Director of the Public Laboratory for Open Technology and Science, known as Public Lab. With a mission of “democratizing science to address environmental issues that affect people,” Public Lab is one of the most innovative and cutting-edge organizations focused on leveraging technology for good while, at the same time, setting the bar for what equitable, just and community-based environmental, social and human health work can look like. Practically, this has led to the buildout of a global network focused on developing DIY tools and technologies that allow communities to conduct environmental monitoring directly, an astonishingly important task at a time when regulatory oversight in the public interest, at least domestically, ranges from a status of perpetually underfunded to outright corrupted. Inspired and forced into action by the 2010 BP Oil Spill and the following information blackout in terms of the extent of the spill, Shannon and her team began with a beguilingly simple approach to monitoring the impact of the spill — a helium balloon-mounted camera and development of an open source platform to stitch the images into a compelling map of the actual scale of the oil slick.

Shannon gave a keynote address at the 2015 Bioneers Conference and was featured on a popular episode of Bioneers Radio (listen at the end of this article). Teo Grossman, Bioneers Senior Director of Programs & Research, recently spoke with Shannon to update the story and find out what Public Lab has been engaged in and accomplished in the past half decade.

TEO GROSSMAN: Tell us about what’s been happening at PublicLab in the past five years.

SHANNON DOSEMAGEN: We’ve expanded substantially. Over the last year especially, we’ve doubled down on our structural work to give PublicLab.org a much smoother user experience. We’ve also been building up a global open-source software contributor community. We’ve built up a really strong and wonderful community of mentors who are helping people new to open-source coding come into the community, and at the same time, we’ve really increased the resources that PublicLab.org has to offer because of all of these new people. We’ve expanded infrastructure, which has allowed more people to come into the Public Lab ecosystem to use the methods and resources that are being posted.

In terms of topics, we are of course very interested in thinking about climate change and the current impacts of the increasing storm systems across the Gulf Coast and the lower Atlantic region.

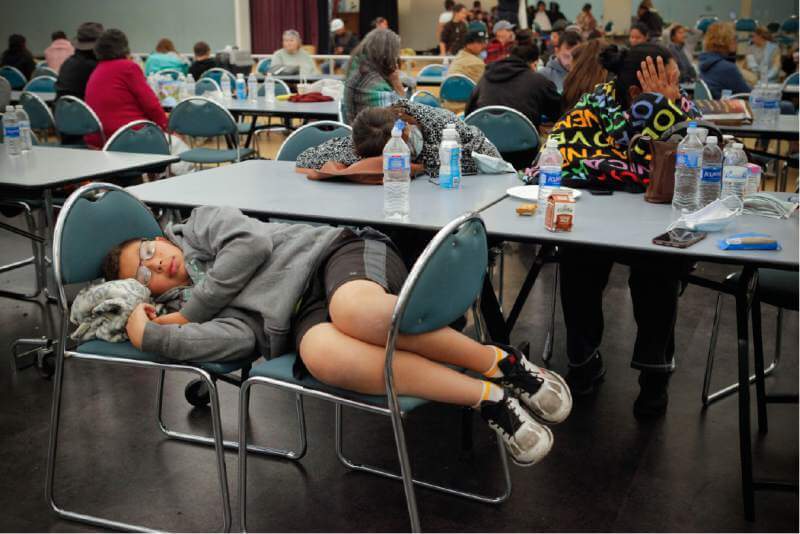

We recently held our annual barnraising, which is our Community Science for Action convening. We took our group over to Galveston, Texas, for a day-long session and one of the bayous in Houston where we talked about disaster resilience, being prepared, and how community science and environmental monitoring can support communities that are facing increasing storm systems such as Harvey and all of the others that swept across the Gulf Coast and the Caribbean a couple of years ago.

In a more daily and local vein, we’re also thinking about how we can support communities being more prepared to live and deal with water, especially in places such as New Orleans and Southeastern Louisiana. The challenges that we face in the Gulf Coast region continue to really be a focus of ours and a place from which we expand our work, ranging from climate change and urban flooding to the oil and gas industry issues that have always been at the heart and core of our work.

We’ve been able to support more and more international projects while building out networks around specific topics. We brought on a fellow for the last nine months who’s been building out The Lead (Pb) Data Initiative. The Lead (Pb) project interfaces between DIY environmental monitoring/community science methodologies and applied work focused on influencing policy decisions on these really important human health issues.

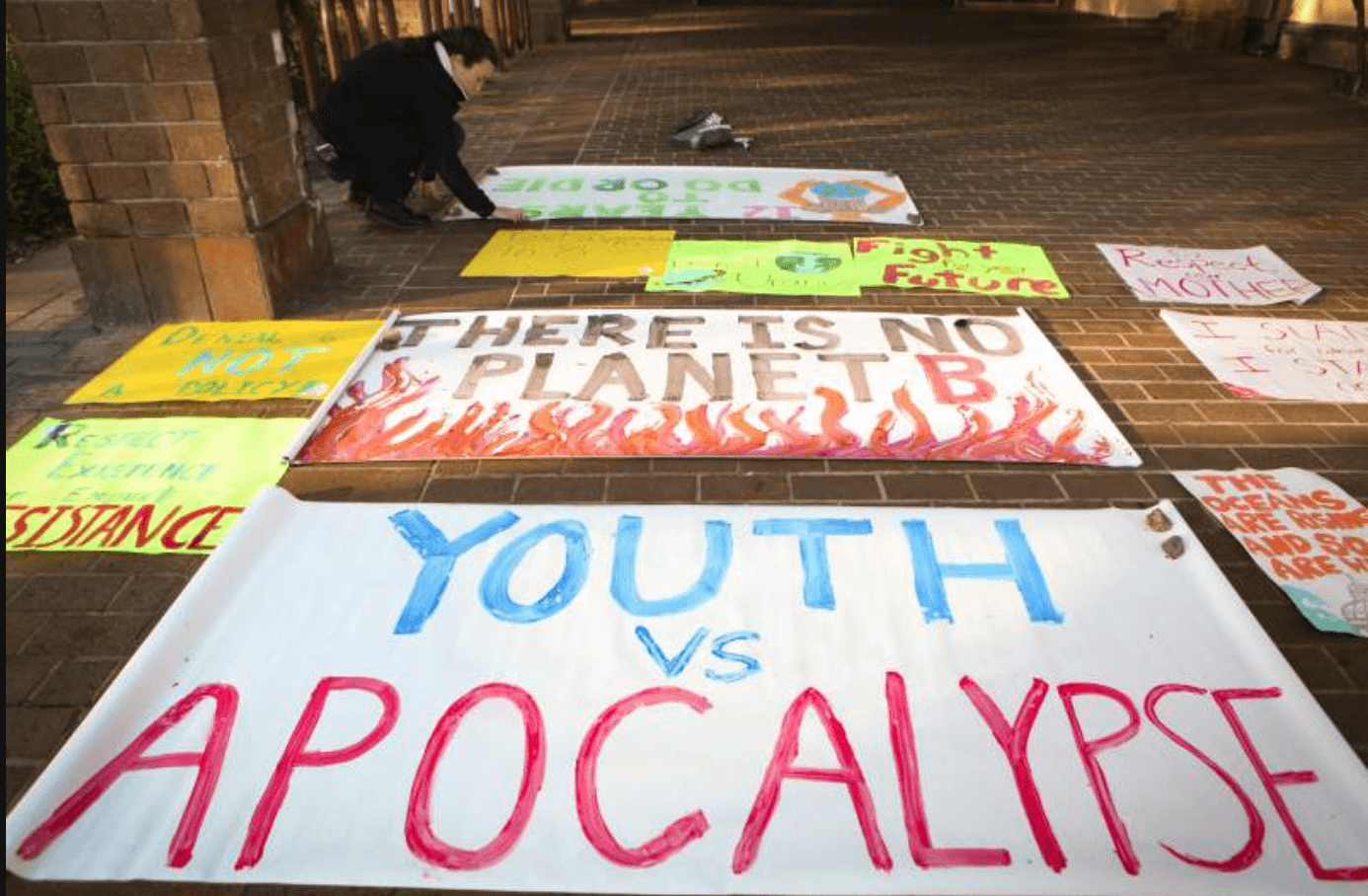

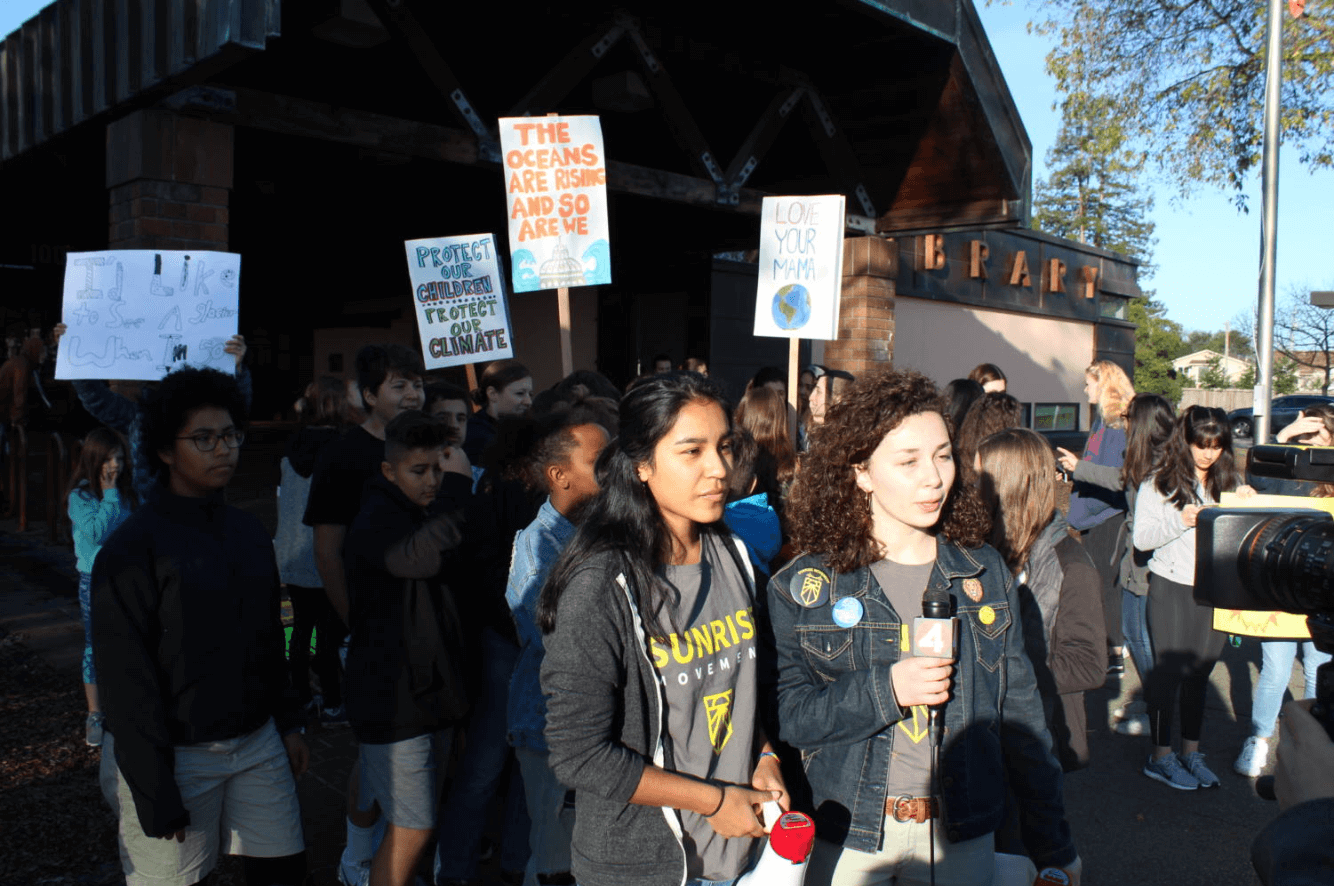

One of the other really exciting things that’s just happened in the last six months is that we have started an Environmental Education program, recognizing that the power of the work that the Public Lab community has been doing for almost a decade now has a place in supporting the next generation of youth by getting them out into their own communities, thinking critically about how to form and ask questions, doing observations, and then looking at data, looking at DIY technology and figuring out how it can answer questions and help youth to become a more engaged and activated in these places that they care about.

TEO: That’s great. Congratulations. When I talk to people about Public Lab, I find that the easiest way to explain it is to start with the actual technology, the tools, and then work back from there towards your broader mission. It seems to be the easiest way for people to wrap their heads around it. In your 2015 Bioneers keynote, you talked a lot about the balloon mapping work, and then noted Public Lab was just getting into air sampling devices and water-monitoring tools. I’m curious if you can share anything about some of the DIY tools, if you’re still leveraging the same ones you’ve used in different ways or if you’ve come up with different approaches as the technology keeps getting faster and smaller?

SHANNON: That’s a great question, particularly in the context of the last half decade. I would say the field of open hardware and DIY technology to support environmental and social justice issues has bloomed in a very amazing way. When Public Lab first came into existence about a decade ago, there were not a lot of other people that were really actively thinking about how to apply open hardware to environmental and human health question asking. In recognition of this kind of change in the landscape and change in the field, Public Lab has tried to take on a facilitation role: How do we help and support people who are thinking about new technology to see it all the way through from the initial idea and pilot to the distribution and actual use?

A year ago we ran a kickstarter for our DIY Community Microscope. It’s a really great tool for obvious reasons – water sampling, for instance, but it can also teach you a lot just in the process of making and putting it together.

We are hosting a new DIY marine microplastics trawler, developed by a researcher named Dr. Max Liboiron, called BabyLegs. We’re partnering with her to figure out ways to support wider distribution of this tool. These are some examples of the projects and tools that Public Lab is bringing in and through our system.

One of the other things that’s happened since I spoke at Bioneers in 2015 is that Public Lab, along with several other universities and organizations, put together an annual convening and community called the Gathering for Open Science Hardware. This group represents people working across the sciences, from community and citizen science all the way to the lab sciences, who are really engaged in making tools accessible through open-source licensing. I think the creation of the group and the fact that we get something like 350 applications every year, from 30+ countries is a really good indication of how much the field has grown in the last half decade, which is incredibly exciting.

Public Lab is also really thinking about how we expand and increase the availability of our methods and our resources that don’t require technology. That’s everything from teaching people how to be better facilitators for the difficult conversations that inevitably emerge regarding environmental and social justice topics to how to actually moderate and facilitate an open kind of unconference-type convening such as our barnraisings.

One of the ways that we’re doing this is bringing in fellows to Public Lab so that we can think about who this next generation of leaders in community science is going to be, and how to work with them productively on these projects. We’re working to expand our resources to younger people, building out models and methods for educators who can bring community science into the spaces in which they’re working.

TEO: How has the field of citizen science and technology evolved in the past half-decade? When we first met, I recall the two of us discussing the need to “close the loop” in citizen science, to focusing on the concept of “citizen” as much as “scientist” – the civic responsibility of using science and data in the public interest. Has progress been made there in terms of democratizing the field?

SHANNON: There have been some really amazing strides in the right direction. Public Lab calls our work Community Science and, at the time, it was an intentional move away from the broader field of citizen science, which was quite top-down and scientist-question-asking driven, but also did not adequately represent our community, people would not always agree with the term “citizen.” We started using the concept of Community Science to indicate a form of work in which science is a thing that can support the organizing activities of communities but is not the only thing that is happening there. There really has been an interesting shift in the last few years. Even if they’re not calling it community science, organizations and projects are starting to ask, “How do we make the work that we’re doing much more responsive to the questions that people in communities are asking about their own places?”

That is really something that I’m happy with because Public Lab has been quite influential in making sure that type of shift is able to happen. There are generally a lot more people who are now aware of equitable practices across all of the different functions of their projects even if they’re not to that perfect point of everything being community driven. They’re really trying to figure out stronger ways to bridge and create partnerships that are truly in the interests of people and communities rather than only scientists or institutions.

Public Lab is very interested in social justice and environmental justice, and I think what we’re seeing is when you are engaged in these community science practices where you’re out asking your own questions and figuring out solutions and answers, it can prompt you to be a more civically active person all around, not just in terms of doing these environmental problem-solving projects but really understanding your own agency, your own power, and the ability to participate and change things that need to be changed.

TEO: When you spoke with us in 2015 for Bioneers Radio we kind of put you on the spot and asked you about your vision for the future. You answered, “I hope that, with the help of projects such as Public Lab, that we’re able to make very simple environmental monitoring as ubiquitous as everyday objects you might find in your home today, such as a smoke detector or carbon monoxide alarms. I’d like to see people able to have that power at their fingertips. I would love to see people being engaged actively and equally as stakeholders, having a place at the table in terms of the decisions that are being made about their communities. And I think we’re going to get there.” Does that still resonate for you? Do you have anything to add? Do you think we’re making good progress along that line? Much can change in five years but in some ways it’s just a drop in the bucket.

SHANNON: The technology angle of what we do still really resonates. There’s just continued growth and youth interest. And open source applies to many different things that fall within Public Lab’s scope, from actual physical hardware devices to opening up data. So I’m happy to see how the world of open source has continued to influence the ability to make these devices, methods and ideas more ubiquitous as we’re thinking about the current and future environmental and human health challenges that we have to face.

The thing I would add that is probably is buried somewhere in there or at least it was buried in my brain as I was saying this, is that we’re really interested in what the human impacts are from many, many different scales. We want to know how a community is impacted by an individual’s ability to be more engaged in the processes that are happening in their neighborhood. We want to know how an individual is changed because they now have a deeper understanding of how science can support the questions that they want to ask in the world.

We’ve really dramatically seen these sorts of changes at all different levels, from individuals we’ve supported to community organizations and nonprofits, to the scientists, journalists and institutionally affiliated academics that we work with. We really have seen a shift in thinking about people-centered science that we’re so passionate about. Open-source hardware ubiquity is fantastic but these kinds of changes within society and how people view their role and their approach, that’s I think really where the cool impact is.