Rebecca Burgess and Fibershed are building a regional economy that connects ranches producing wool with artisan clothing manufactures. Fibershed’s local economy network is based on carbon farming practices that capture atmospheric carbon and store in the soil. Soil carbon supports a regenerative fertility cycle and is the building block for a climate-friendly life-promoting economy. For more information go to the Fibershed website: https://www.fibershed.com/

Healthy Soil and Environmental Justice in California’s San Joaquin Valley

By Janaki Jagannath

Janaki Jagannath is an advocate for farmworkers who, as the former Coordinator of the Community Alliance for Agroecology, works to advance environmental justice in California’s San Joaquin Valley where chemical farming continues to impact the health of rural communities. She gave this talk, transcribed and edited below, as part of the Bioneers Carbon Farming series. Jagannath is currently in law school at the University of California at Davis.

Protecting the health and diversity of soil microbial communities is the first step to protecting the health and diversity of the human communities.

In California’s San Joaquin Valley — home to many of the nation’s largest fruit, nut and vegetable operations — agricultural soils have been sterilized and depleted of natural fertility. This trend in agricultural soil management is standard practice for industrial farming, and while it’s still possible to turn the trend around and begin managing soils to improve the health of the region, doing so will require us to examine the history of environmental justice (and injustice) in California.

Environmental Justice & Injustice in California

In the 1990s, President Clinton signed Executive Order 12898, Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations, a set of policies that required federal agencies to ensure the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin or income with respect to the environmental impacts of the development, implementation, and enforcement of federal programs and policies.

Among other state programs and policies that have been advocated for and created by environmentally burdened communities of color, the California Environmental Protection Agency has released CalEnviro Screen, a mapping tool depicting communities that are impacted by cumulative environmental impacts such as groundwater pollution, ozone, particulate matter, pesticide exposure, and other toxic pollution. Under Senate Bill 535, California directs 25% of the proceeds from its Cap and Trade program to climate investment funding in those zones which are most impacted.*

These communities suffer the problems that arise from historic land-use policy in California, which has essentially been created by and for large agribusiness, and rarely prioritizes soil health or community health. Rather than building carbon and organic matter, the soil has been stripped of most of its life, and nutrients such as phosphorus and nitrogen get added back in through synthetic fertilizers.

As a result, over one million California residents are exposed every year to water that is unsafe to drink by state standards. In addition, many communities lack adequate wastewater infrastructure, housing, and perhaps most importantly, effective governance. Many environmental justice communities are places that were settled during the migration that took place when the agriculture of the Midwest was pushed to its limit resulting in the Dust Bowl. A period of dramatic expansion of the fruit and specialty crop economy in California led thousands of migrants from across the country to move to California as field workers and packers.

During World War II and with the implementation of the Bracero program, Mexican farmworkers and other communities of color moved into and continued to build these small California communities. Wells were dug by hand and when electrification took place it was often done without proper oversight. Land-use policies were historically discriminatory. Since then, larger municipalities haven’t annexed these places and provided them with basic protections for their drinking water and air quality. These rural unincorporated communities face a lack of local governance and some of the most acute environmental and climate impacts in the state.

Today’s Reality

In unincorporated farm worker communities, residents deal directly with harmful impacts of agriculture. Parents send their kids to school knowing they’re going to get exposed to pesticide drift. They are dealing with chronic disease, asthma and valley fever— a deadly infection caused by a fungus found in soil — on a regular basis.

Drinking water in the San Joaquin Valley primarily comes from groundwater wells. The area’s ground water is often contaminated with nitrates, selenium, arsenic, and 123-TCP – a heavy carcinogenic chemical that was recently regulated for the first time. These water contaminants are pesticide and chemical fertilizer byproducts, or simply the products themselves, washed away into the aquifer. This is a direct result of the way that the soil in the area has been treated over time by chemical-heavy farming practices.

The crops are mainly irrigated with surface water. There is a constant lobbying effort by the agriculture industry for access to more surface water because ground water is expensive to pump and often contains large quantities of salt, which is the primary concern for farmers. Meanwhile, ninety-five percent of the water going to people’s homes is groundwater.

There has also been an enormous loss of native vegetation in the Valley because the agricultural industry has removed most of what was left of the native plants, animals and people. We have lost nearly all ecological memory of the area to privatized industrial-scale agricultural landholding.

Moving Forward

A few important examples of alternative agriculture stand out. In Tulare County, an area known for its conservative approach to large-scale agriculture, Steven Lee of Quaker Oaks Farm is working to educate the local community on the importance of building soil carbon as a foundation to achieve environmental justice priorities. A recent recipient of funding through the Healthy Soils Initiative, Steven is planning to pilot a number of soil improvement practices on his land and gauge their ecological benefits. Quaker Oaks Farm shares historic ground with the Wukchumni Indian tribe of the region, and also with farm working families of Oaxacan origin who utilize a portion of the land for subsistence farming.

Community Alliance for Agroecology has built a framework based on ecology that prioritizes the protection of the water and air and other environmental media in addition to building political power because we believe historically underserved communities who have built our agricultural economy should have a say in how agriculture moves forward in our state. Healthy soil protects our waterways, our local air quality and displaces chemical fertilizers and pesticides if built as a part of a natural soil fertility regimen. This has both short and long-term benefits.

We are at a point in California history where we need to be linking arms around the protection of our soil. We have a State Water Board, and a pesticide department, but we don’t have any direct oversight of our soils at the state government level. The health of our soil has been largely left to the discretion of private land owners. Soil is the basis of our food system and we need to be protecting it—especially in the areas like the San Joaquin Valley. To do that right, we must also include the voices of rural people of color and others who have been historically left out of the decision-making process around farming and land ownership.

To learn more about Janaki Jagannath and her work, read this in-depth profile from Civil Eats.

* To learn more about SB 535 and the 25% of California’s Cap & Trade revenue going to disadvantaged communities, please watch Vien Truong of Green for All on Creating an Equitable Environmental Movement.

5 Videos to Watch This Weekend

If you’re anything like us, you need an occasional break from the steady grind of political news to focus on solutions and to find inspiration. As Bioneers, we’re fortunate to be able to connect with a nearly endless list of innovators and thought leaders — people who have identified major world challenges and heeded the call to do something about them.

Year after year, we bring a sampling of these amazing changemakers to the Bioneers stage, where they share their ideas with people like you who are seeking answers and ideas. And we always discover that, while the challenges we face are significant, the power we have as a collective is stronger.

Below, we’ve collected five Bioneers presentations that our audience returns to time and time again. Watch them this weekend, and share the ones that move you with others who seek inspiration.

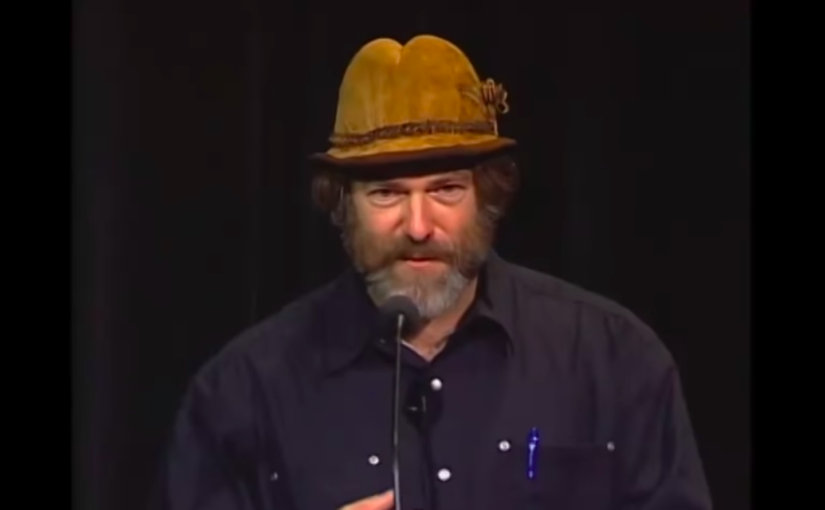

1. Paul Stamets – Mushroom Magic

Paul Stamets, visionary mycologist extraordinaire, has discovered several new species of mushrooms and pioneers countless techniques in the field of edible and medicinal mushroom cultivation. He has achieved remarkable results cleaning up dangerous toxins using “fungal bioremediation” and radically improving soil fertility with mushrooms.

2. Dr. Gabor Maté – Toxic Culture

The Canadian physician and best-selling author of In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts is a brilliantly original thinker on addiction, trauma, parenting and the social context of human diseases and imbalances. Contrary to the assumptions of mainstream medicine, he asserts that most human ailments are not individual problems, but reflections of a person’s relationship with the physical, emotional and social environment, from conception to death. Mind and body are not separate in real life, and thus health and illness in a person reflect social and economic realities more than personal predispositions. In other words, personal responsibility cannot be separated from societal responsibility and changing the world.

3. Severn Cullis-Suzuki – Remember the Future

Severn Cullis-Suzuki, daughter of David Suzuki, graduated from Yale with a B.S. in ecology and evolutionary biology, and is on track to outpace her father as an activist. She founded a children’s environmental group at age 9, addressed the Rio Summit at age 12, and hasn’t stopped since, starting several groups and projects and becoming a dynamic, luminous light in a new generation of eco-leaders. Severn discusses our responsibilities toward future generation; how to heal our disconnect from nature and each other; and how to draw from the best of ancient traditions and modern innovation to build a sustainable future.

4. Naomi Klein – This Changes Everything

The award-winning Canadian journalist, international activist and best-selling author (The Shock Doctrine, No Logo) depicts climate change as more than an “issue.” It’s a civilizational wake-up call delivered in the language of fires, floods, storms and droughts. It demands that we challenge the dominant economic policies of deregulated capitalism and endless resource extraction. Climate change is also the most powerful weapon in the fight for equality and social justice, and real solutions are emerging from the rubble of our failing systems.

5. Jeremy Narby – Intelligence In Nature

In this mesmerizing talk, Jeremy Narby shares the findings from his groundbreaking book Intelligence in Nature. He describes his quest around the globe to chronicle how leading-edge scientists are studying intelligence in nature and how nature learns. He uncovers a universal thread of highly intelligent behavior within the natural world, and asks the question: What can humanity learn from nature’s economy and knowingness? Weaving together issues of animal cognition, evolutionary biology and psychology, he challenges contemporary scientific concepts and reveals a much deeper view of the nature of intelligence and of our kinship with all life.

Under The Skin, We’re All Kin: Reading the Minds of Animals

Calling someone an “animal” means they’re less than human – not worthy of respect, rights, or even of life itself. But in truth — and in biological fact — human beings ARE animals. Scientists continue to find that intelligence and what we call “consciousness” appear to saturate all of nature. Clearly it’s high time to think differently about just what it means to be an animal. Can we know what it’s like to be other-than-human? How can we see into the minds of animals? Visionary naturalist, author and conservationist Carl Safina says that the first step is paying attention and observing. And, he suggests, if we had humility, we’d have everything.

Explore our Intelligence in Nature media collection >>

Artist Lisa Ericson on Surrealism and Nature

Terrarium II by Lisa Ericson

Painter Lisa Ericson has been described as “a multi-hyphenate, utilizing her visual talents as an artist, illustrator, and designer to craft meaningful images.” Based in Portland, OR, Ericson’s enthralling artwork manages to be simultaneously hyper-realistic and wildly imaginative. In many ways, this perspective exemplifies precisely what is needed to surmount many of the most pressing issues facing us today: a combination of pragmatism and creativity. Her clear love and admiration for nature’s intricate genius is immediately apparent when faced with her work. Bioneers has annually chosen an artist and piece of artwork to provide the look, feel and visual inspiration for our annual conference. We were overjoyed when Lisa was willing to donate an image of her painting, Terrarium II, to Bioneers as the featured image for the 2018 annual Bioneers Conference. Terrarium II is part of a series of paintings displaying different species of turtles carrying collections of ecosystems on their backs. The images evoke beauty, bounty and fragility and one can’t help but recall creation stories of many Native American tribes that refer to our collective home as Turtle Island.

Bioneers caught up with Lisa following the conclusion of her recent show at Antler PDX to talk about her art and her life as an artist.

BIONEERS: How long have you been an artist? Where did you go to school or get your formal training?

LISA ERICSON: I got serious about art in high school and went on to major in painting at Yale. I struggled to find the time and energy after I left school to pursue art outside of my regular non-art related job and ended up not doing much painting for about ten years. I took classes in graphic design and spent time doing freelance graphic design and website design work, but eventually, after that lost decade, I found my way back to painting. This time around, older, hopefully wiser, when I had a chance to get back into painting, I didn’t look back. That was five years ago now and I’ve been working steadily ever since.

BIONEERS: Where does the magical realism come from?

LISA: I like to take the wonder of the natural world and tweak it just a bit. I enjoy the play of the hyper-realistic way I paint and the surrealistic subject matter.

BIONEERS: Can you talk a little bit about your process, praxis and theory?

LISA: Well, I paint from photographs and I have a rather lengthy and intense process of putting together a composite image to I work from. I work out my ideas, as well as composition, light, and color during that time. When I’m happy, I print out the composite image, transfer the sketch on to a panel and start painting. I work in acrylics and I always start by painting the black background, leaving the white under the image so it has a much light and glow as possible when it’s fully painted. I usually do an under-layer, getting the basic color/values down. Then I do an intensely detailed final layer.

BIONEERS: Are your images meant to bring awareness to “environmental” issues?

LISA: Yes. Although my pieces are far from scientific – I take whatever liberties I feel a piece needs – they often have their roots in current environmental issues. The whole series of mini mobile coral reefs connected to fish began after I read about the massive bleaching incidents happening on the Great Coral Reef a few years ago. The series of mobile habitats on the backs of turtles started with ideas of animals being displaced from their habitats due to climate change or other human-related factors.

BIONEERS: What is your favorite accomplishment as an artist?

LISA: Maybe it’s because of my history, but I feel a sense of accomplishment and deep satisfaction whenever I finish a piece. My favorite time with my work is when they’re all hanging up in my studio before a show.

BIONEERS: Who are some of the artists that you’re excited about at the moment?

LISA: I think Jeremy Geddes is pretty phenomenal. I love Tiffany Bozic’s work. And I admire the work of a lot of the artists in my own Portland art community – Josh Keyes, Zoe Keller, David Rice – as well as some of talented people I’ve shown with – Josie Morway, Lindsey Carr, Vanessa Foley.

BIONEERS: Why did you decide to donate to Bioneers?

LISA: I don’t think there are many issues more important right now than taking better care of our planet, and I love the idea of using nature’s own systems as inspiration for human ingenuity.

Thanks to Lisa for the interview and use of her images. Be sure to check out her website and Instagram.

Young Climate Activist Dissed By Gubernatorial Candidate: An Interview with Rose Strauss

On July 18th, Rose Strauss, an 18 year-old college sophomore, attended a Town Hall meeting near Philadelphia hosted by Pennsylvania gubernatorial candidate Scott Wagner (R). Strauss asked Wagner a question about campaign donations from fossil fuel companies. His response, calling her young and naïve, made national news.

Rose Strauss and her colleagues responded rapidly, leveraging Wagner’s remarks into action to support the vital effort to get fossil fuel money out of politics. Al Gore recently tweeted, “If being ‘young and naive’ is holding our leaders accountable and demanding a sustainable future, call me #YoungAndNaive.” Recent numbers show a boom in youth voter registration, with registered voters under 35 outnumbering those over 64 in Pennsylvania.

Bioneers first met Rose Strauss when she was awarded a Bioneers Youth Leadership Scholarship to attend the Bioneers Conference as part of a cohort from the Marin County Youth Commission. Arty Mangan, Director of the Bioneers Youth Leadership Program, spoke with Rose recently.

ARTY: Pennsylvania gubernatorial candidate Scott Wagner said “You are young and naïve” when you called him out in public about the $200,000 in political donations that he received from the fossil fuel industry, and his statement that climate change was a result of people’s body heat. How can you cut through the corruption of politicians and the cynicism of the people who think like that?

ROSE: Politicians say these kinds of things because they’re being funded by people with fossil fuel objectives. It’s good for them when the public is uneducated. Mr. Wagner is perpetuating these lies because he’s being funded by fossil fuel executives.

I am part of the Sunrise Movement. We think a great way to stop that from happening is by making sure politicians are not taking contributions from the fossil fuel industry. At Sunrise, we have a No Fossil Fuel Money Pledge to get politicians to commit to not taking money from fossil fuel executives or front groups.

ARTY: During this incident, there was laughter and applause when Wagner condescendingly called you “young and naïve.” Yet in a Teen Vogue article you wrote that the incident left you feeling empowered. How do you explain that?

ROSE: It left me feeling empowered because I spoke up to someone who has power and was talking down to me. His response was so demeaning and so patronizing, but at the same time so ridiculous that I was excited that we could turn that response and his perspective and his words into something that a lot of people would see. They’d know that this politician has these beliefs. It was empowering, knowing we could take what he said and turn it into a call to action.

ARTY: You’ve really done that. In the Teen Vogue article, you also wrote, “Fossil fuel executives and lobbyists get away with their pay-to-play politics because they corrupt our democracy in the shadows, and it’s our role to bring their actions to light.” Speaking truth to Scott Wagner is an example of that. How do you plan to do more of that in the future?

ROSE: A big thing that we do at Sunrise is canvassing and talking to people. I think that’s one of the most impactful things you can do. Politicians and fossil fuel executives have millions of dollars, but what we have is people power. We can counteract the power of money by talking to people, educating them, making sure that we’re standing up for what we believe in, and making sure that climate change is a central issue that’s being solved. Canvassing is a really great way to do that, as well as registering people to vote. Ultimately, we choose our politicians. Educating the general public about climate change and the political system is so important.

ARTY: What is the Sunrise Movement? What are its goals?

ROSE: Sunrise Movement is a movement of young people fighting to solve climate change. We do this by ending the corrupting influence of fossil fuel executives on our politics. This includes things like confronting politicians at Town Halls, like I did, or at public events to challenge them to take a better stance on climate change.

We also get politicians to sign a No Fossil Fuel Money Pledge, as I said before, which over 800 candidates and other politicians have already signed.

We also are working to make climate change an urgent political priority. Another way that we do this is by electing leaders who we think will fight for our generation’s future. I’m in Downingtown, Pennsylvania, where we’re working to get Katie Muth and Danielle Otten elected. They take really strong stances against climate change and also have signed a No Fossil Fuel Money pledge. We’re canvassing to get them into office. That effort is youth led.

ARTY: How did you become a climate activist?

ROSE: Ever since I was young growing up in the Bay Area, I have always had a really intense love for marine biology and the ocean. Climate activism was a natural segue for me, going from loving animals to seeing them disappear faster than I could study them. My focus shifted from studying the biology aspect of it to focusing more on conservation; that eventually led me to this climate change fight.

The first time that I was exposed to climate change was looking at the impact on marine systems. I started Bay Area Youth for Climate Action. We focused on educating youth about politics and how they can make a change, and we worked hard on the campaign to get coal out of Oakland by hosting conferences and doing outreach and education to youth around the Bay Area.

Going away to college, I was looking for something where I could be politically engaged in fighting for climate change, and Sunrise was just the perfect opportunity for me. When I saw the ad on Facebook for Sunrise, I was like, “I can’t not do this. I have to go.” So here I am. Sunrise has seventy Fellows who are working on the midterm elections. There are also different hubs all around the country that are working with Sunrise. It’s a pretty big movement.

ARTY: There’s no doubt that the world is a challenging place. There seems to be a new crisis on a daily basis, and the climate issue is certainly one of, if not the largest, crises that we’re facing. As a young person, how do you maintain a positive view of the future? What’s your advice to other young people?

ROSE: I think it’s really easy to get a nihilistic attitude toward the future. If you look at the science closely, climate change has pretty dire impacts on the Earth, if we don’t do something about it relatively soon. But I think that it’s important to look at all of the technology that we have and imagine a world in the future that’s run on renewable energy and exists in conjunction with nature. I think that’s something that’s possible, and it’s something we need to continue to work towards. Envisioning that future is really inspiring to me.

Also, keep with the movement, stay with a group of people who also are working on this issue, because it’s really easy to feel super alone when you’re working on climate activism, especially if you’re not around people who care. Finding a group of people who also care will inspire you and keep you going. Join the Sunrise movement or a similar movement in your community.

ARTY: How can more young people be activated in the fight for climate justice?

ROSE: I would say look at community. A lot of people don’t realize that there are environmental justice and climate justice issues happening right in front of them. I find it’s a lot easier to organize people around intersectional issues, not just climate change. People who are into feminism or are into LGBTQ issues or immigration, you can take that group of people and take that passion and connect it to climate change, and work on it in a super intersectional way.

For more people wanting to get involved, find issues in your community, and start something. You can start a campaign and get involved with local politics. Make sure your voice is being heard, because living in a democracy is a privilege and you have to take advantage of that. That’s a super important thing to do. Vote.

ARTY: When you talk about intersectionality, I think about the comments by Wagner. He disrespected you on multiple levels: as a young person, as a woman, as a knowledgeable activist. When you stood up to him, It uncovered multiple biases of his. Was that a strategic move planned by Sunrise or was that your individual action?

ROSE: We planned on going to the Town Hall, and I was planning on asking the question. That part was definitely planned. We did not plan for the response he gave, but as demeaning and shocking as it was, it was also a really great way to get people involved with what we’re doing.

ARTY: What do you see as the best solutions for climate change?

ROSE: I think the best solutions are getting fossil fuel money out of politics. That’s a really important one because once that happens all of the other options that we have for climate change will start being turned into policy and legislation. We can see that happen because we have the technology. We have renewable energy that works, but the big issue is that we have these political barriers. We need people power to push it forward over fossil fuels. That’s a super important step.

ARTY: You were a Bioneers youth scholar a few years ago, did that experience have any influence on your activism?

ROSE: It definitely does. I was super inspired by everything I heard at Bioneers. It taught me more about climate change, and one thing that really struck me—I’m not sure exactly who was speaking—but the person was talking about the power of story. That really changed the way that I talk to people about climate change. That’s a big value that Sunrise holds, using stories to change people’s minds instead of just facts. That’s something I really got from being at Bioneers, which was awesome.

ARTY: What is your message to your generation?

ROSE: To all the young people out there, keep fighting, keep getting involved, we’re creating a movement, I feel the energy right now, and I feel like there’s a shift in energy. I feel like we’re actually making some real progress. So many young people are starting to become engaged with climate change activism. We need to keep this momentum going.

Hope Where It Counts: How a 25 Year-Old Activist Moved Into Local Politics

Coming on the heels of the 2016 Presidential election and the Women’s March, 2018 has seen a record number of women running for political office at local, county, state and federal levels. Recent primary victories by Stacey Adams in the Georgia gubernatorial race and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in the 14th District in NYC have made headlines. These are national races but the same movement is taking place down-ticket at the local and state level, where policy decisions that often impact people the most on a day-to-day basis are frequently made. In June, Chloe Maxmin won the Democratic primary race for state representative in her home district in Maine. Maxmin is all of 25, a young woman running for office while many of her peers are beginning graduate school or trying to sort out a career. For Maxmin, however, who began organizing at 12, this is simply the next logical step in her mission to build a social movement that speaks for her generation.

Bioneers was honored to host Chloe Maxmin as a Youth Keynote Speaker in 2014, fresh off receiving a Brower Youth Award. She discussed her leadership of the Divest Harvard campaign, a complex effort that marked a major turning point in the overall Divest/Invest movement, which now counts nearly $6 trillion in assets divested, thanks in many ways to passionate organizers like Maxmin who pioneered the movement on college campuses.

Bioneers caught up with Chloe earlier this spring to discuss this latest step in her powerful journey to change the world by empowering youth to lead the way.

CHLOE: My name is Chloe Maxmin. I’m 25 years old, and I’m from a small town in Maine. I have been a climate justice organizer for 13 years, since I was 12 years old, and that journey has brought me to a lot of different places. Where it’s brought me right now is to an understanding that we need profoundly effective and powerful social movements to influence our political system, and we need really strong politicians in office to respond to those movements and enact the kinds of policy changes that we need.

BIONEERS: Can you give us a little insight about how that path led you to where you are now?

CHLOE: It’s been a long, winding road. This has been in the back of my mind for a while, but only in the front of my mind very recently.

When I first started out with youth activism and organizing, my focus was very local and it was based in my hometown. I did a lot of work in my high school to get my peers involved with climate justice work and talking about climate change and environmental issues in our community. I started the Climate Action Club at my high school. We did very individual-based work, looking at questions like, “How can you as an individual change your habits and how can we as a school and as a community change our habits so that we’re reducing our impact on the environment?” I learned a lot. It was my first foray into organizing.

But when I got to college, I went through the traditional radicalization process and began to understand that this is a system problem and it’s hard to blame an individual for a system problem or for an individual to confront a system problem. The way that we do confront system problems are with mass movements that build collective power around an issue, and calling on our politicians to respond to that political energy.

I worked on the fossil fuel divestment movement for a long time. I started Divest Harvard, which began with three people and grew into 70,000 strong by the time I had graduated. Divestment was very formative for me because I see it as a more systemic form of organizing. The theory of change behind divestment is that you’re divesting from the fossil fuel industry because you want to increase the stigma so that politicians are less likely to interact with that industry to take money. Divestment is trying to create a new political space and then the idea is that people will then infiltrate that new political space and push forward climate policy. [Editor’s Note: see Bill McKibben’s recent article in Rolling Stone for a deeper dive into the current state of divestment.]

One of the things I noticed as the divestment movement progressed is that the movement was really strong, but we weren’t really pivoting to take advantage of that new political space that we were creating. I wrote my thesis on why the climate movement wasn’t being effective politically in the way that we wanted and the way that we needed, because whether we like it or not, we need politics to solve this crisis.

I learned a lot about how social movements are structured, and how we don’t really like to engage with political systems or with electoral politics. This is a big discontinuity to me because, as I just said, we really do need politics to catalyze the systemic change that we see and need.

I moved back to Maine after I graduated from college to build political power for climate justice because I really think that Maine can be a powerful, bold climate leader. We’re the most rural state in the country. The county that I live in (and is part of my district) is the most rural county and oldest by age in the nation. We have a lot of really unique challenges here which means we can also be a leader in developing really unique solutions for rural places that are confronting climate change and being impacted by climate change.

I still organize and I’m still a grassroots organizer as I campaign. But there’s a really big part of me that is just really tired of begging people in power to listen to me, to listen to my generation, to listen to everybody in my community who are struggling to heat their homes, to feed their families, to ensure that their farms will survive as the weather gets more and more chaotic. I think that we need a new kind of politics that is responsive to the people and always stands in solidarity with the community that politicians come from. And I think that young people are perfectly poised to lead that new wave of political energy.

BIONEERS: What is the dialogue that you use to move your community and help them shift themselves on a personal level?

CHLOE: Organizing in Maine is a very unique experience because it is such a rural place. Organizing is built on connecting the people and building relationships and it’s just a lot harder to do that when you have to drive every place or you don’t have access to transportation. A big part of what I try to focus on here is developing new models for rural organizing in a place like Maine.

I think one of the key messages that I talk about, which I truly believe in, is that this is about our shared love for our home and our community, the land and our way of life, and the people that live here. It’s not about believing in climate change or not. It’s about, “Do you care about where you live?” People do because they live here. How can we use that as a shared foundation to move forward and build your work together?

BIONEERS: It’s so important to connect with the community. I think a lot of times politicians and policy makers don’t take the time to connect with community, and they don’t recognize that each community is unique, has its own culture and own approach, and its own way of getting in touch with the people.

CHLOE: If I could add one addendum to that, based on the conversations I’ve had with people in Maine and in my community. There’s so much disillusionment around what we can do at the federal level to stop all of this destruction that we’re seeing. In Maine right now, our governor is a very right-wing Republican who has also championed a lot of destructive policies in our state. For us there is also little hope at the state level.

For example, Governor LePage has almost completely decimated the solar industry in Maine through his policies. Luckily we’re getting a new governor this year, so we can right that ship and not all hope is lost.

But there is hope at the local level and I have found that to be a constant source of inspiration for me and folks that I’ve been organizing with because we can tangibly see the difference that we’re making, the movements that we’re building. We can interact with the people who are in positions of making decisions, build really meaningful relationships with them and really change the way that our community operates and thinks about different issues. So it’s all about the local.

BIONEERS: Among other past achievements, you spoke at Bioneers and won a Brower Youth Award. What did you gain from those accomplishments?

CHLOE: The biggest thing that I gained from those experiences were meeting incredible young people who are doing incredible work in their communities. Their vision and their energy, it’s just so inspiring.

One of the things that I really admire about so many of the young people in the Brower and the Bioneers networks — and so many of the young people doing change-making work right now — is that we’re growing up in an age where everyone who we’ve been told are our traditional authority figures, whether governors or presidents, are failing us. They’re not doing what’s right and they’re not fighting for the people. As young people, we could say, “Oh, but they’re the people in authority, we should defer to them because they know what’s best.” But instead this entire generation of youth is saying, “No, what you’re doing is wrong, and we know what’s right. And, yes, we’re young, and, yes, we’ve lived less years than you have, but we have our own type of expertise, and the foundation of our expertise is a moral clarity that cannot be shaken by anybody.” I think getting into spaces where you can experience that kind of passion and purpose is incredible, and I definitely experience that with Brower and with Bioneers.

BIONEERS: Along those lines, how has being a young woman, aspiring to get into local politics, shaped you on a personal level and have you encountered any resistance?

CHLOE: I think what really grounds me in the work that I do and has been the constant throughout my whole life is that I so deeply love and care about my home and my community. That is my core motivation. No matter what happens or who doesn’t want to vote for me or who doesn’t agree with my tactics, that’s okay. It takes all kinds to make the world go ‘round and we need all different kinds of perspectives. But I know in my core what my purpose is and that can’t be shaken.

I feel really lucky to know that about myself. All of us have things, people, places, ideas, causes, pets that we love and care about and are willing to fight for as well. This is something that I talked about when I was at Bioneers. If this is the core motivation of our work, then it’s hard to get sidetracked because we know what we’re fighting for and what our purpose is and it’s coming from a place of love, not from a place of anger or fear.

It’s still early in the campaign, and there’s been some resistance and skepticism, and that’s okay, but I know what I stand for, and I know what I care about, and I know that I will devote my life to this community no matter what happens. That’s all that really matters to me. I’ve been really lucky to have so much support from my friends and family, and from people who hopefully will be my constituents one day. It’s going to be okay.

BIONEERS: I would love to hear about your thoughts on youth voices, the power of that approach, and how you bringing in youth voices to your own campaign.

CHLOE: My entire life I’ve been represented by people who aren’t my age and while those people have been really good politicians, why can’t there be someone my age in office? I think the people who represent Mainers, Americans in any representative political system, should reflect the people who live there.

It’s not just about young people though, it’s about fighting for everyone who lives here right now but youth can be a platform to unite people and create really inclusive platforms. Because it is about everybody, and I think it’s time that we get some young folks in office.

It’s happening all over the country. It’s happening all over Maine. I’m just excited to be part of that movement in my little district.

BIONEERS: Do you have any advice for young people or activists of any background or any age on how to take that first step, how to move past fear, and how to align themselves in a way that’s most authentic for them, how to get started in this journey?

CHLOE: It’s so different for everybody. For me, the foundation of everything is coming from my core motivation and my place of passion. I think finding that place and using that as the rock that you stand on gives you the power to really do anything that you want to do.

I also think it’s really important to have people around you who support you. I couldn’t do this without so many people in my life, in this campaign. The movement of young people running for office is not just about us as individuals but about this generation and about everything that we care about today and the future.

If anyone ever wants to reach out to me to talk about this stuff, just Google me. You’ll find my website and you can just email me.

Biophilic Cities: Embracing the Optimistic Future of Natureful Cities

By JD Brown, Biophilic Cities Program Director

At Biophilic Cities we are nurturing a growing network of partner cities that are working collectively to pursue the vision of a natureful city within their unique and diverse environments and cultures. Applying E.O. Wilson’s biophilia hypothesis to the scale of planning and designing cities, biophilic cities recognize that humans have co-evolved with nature and require a daily connection to nature for our overall health and happiness. This is a vision that embraces the understanding that humans are not separate and apart from natural living systems. The world has entered into what has been termed the “urban century” as increasing global populations congregate in cities. While this growth presents obvious challenges, it also presents an opportunity to provide meaningful access to nature for populations that traditionally have had the least access to nature and where such access can have an exponential positive impact on health, well-being and quality of life.

Credit: Curridabat

There is no single model for a natureful, biophilic city. The Biophilic Cities Network is a diverse set of partner cities that draw solutions from their varied experiences, cultures and landscapes. The vision of Phoenix, Arizona as an arid city rich in nature is one that embraces its native, xeric landscape. This vision is very different from that of Singapore, a “city in a garden”, that is lush in green vegetation.

In Curridabat, Costa Rica, the city is transforming itself into “Ciudad Dulce” (Sweet City) by cultivating pollinator habitat across the urban landscape. This initiative, under the leadership of Mayor Edgar Mora and with the support of broad public and private partners, has received international recognition. It embraces the health benefits that result with the creation of nature-based infrastructure. In particular, the initiative aims to create new opportunities for access to nature in economically marginalized communities and to engage these communities in the co-design of public “sweetness spaces”.

In Wellington, New Zealand, a coalition of partners that includes local government is undertaking an ambitious effort to increase the biodiversity of native song birds across the city through a campaign entitled Predator Free Wellington. Through the control of invasive predators, the effort seeks to reclaim the city’s pre-human biodiverse origins. Two decades ago, a 500-plus acre predator free sanctuary on the outskirts of the city called Zealandia was established with dramatic resulting increases in native biodiversity. From this early success story, communities across the city have embraced new found opportunities to experience seemingly lost biodiversity and the result is an unprecedented level of civic ecoliterarcy and engagement in conservation efforts.

In Pittsburgh, the city has established an EcoInnovation District, the first of its kind, which seeks to invigorate underutilized commercial districts by planning and designing a neighborhood that is rich in opportunities to access nature. Biophilic include the reuse of vacant lots, improved access to fresh food through community gardens, and the planting of new trees and green infrastructure to capture stormwater and reduce the heat island effect. The project was recognized by C40 Cities in its report Cities100 for creating local solutions for climate change. The EcoInnovation District is one project among many that the city is pursuing to address the impact of its industrial history.

This is a small sample of how our partner cities are designing and implementing initiatives that bring nature into their cities as a source of healing and source of inspiration. Important lessons are learned and shared as the partner cities convey their experiences and collaborate in an effort to broaden the scope of how and where human-nature initiatives are implemented.

The Strength of the Network

There is tremendous value in the Biophilic Cities Network as a central organizing structure to address complex societal challenges. A resilient network includes engaged, yet dispersed connections across organizations and individuals pursuing solutions through a diversity of ideas and approaches. The result is the ability to tackle complex challenges that do not fit neatly into a single subject category and require multidisciplinary solutions.

Planning and designing cities with abundant opportunities for human-nature interactions is more complex than it might appear. For example, how to do we create wonderful parks and trails in communities that lack these amenities, and would benefit the most from their creation, without raising property values and driving existing community members away? How do we create greenspaces that are open to the public but not fully occupied by growing populations in need of places to live? These are complex problems impacting cities that require addressing fundamental societal concepts like public access, sustainable economic development and affordable housing. These challenges require drawing ideas from varied expertise and experiences.

Building the Scholarship Behind Biophilic Cities

Located within the University of Virginia, Biophilic Cities brings a multidisciplinary approach to facilitating the network’s collaboration and developing the scholarship underlying the vision of biophilic cities. This includes engagement with organizational partners whose work, in areas such as public health, community resiliency and sustainability, is complemented by applying a lens of biophilia.

Our scholarship includes an investigation of forward thinking legal codes and mechanisms that exemplify successful, innovative legal tools and policies adopted by global cities to promote abundant and accessible nature. These Biophilic Codes are varied in their focus and approach but from which we draw consistent themes; themes that can be applied more broadly.

For example, in San Francisco, a homeowner concerned with stormwater flooding in her basement, as a result of run-off from paved surfaces, petitioned the city to convert some of the double-wide sidewalk outside her home into a vegetated landscape and natural stormwater buffer. The city granted the request and the result was a successful pilot project. The petition became the foundation for a sidewalk landscaping permit program administered by the city through which residents can apply to similarly convert paved areas into biophilic features that augment the street landscape and control and treat urban stormwater.

Washington, DC has adopted landscape and design standards for new development with the goal of increasing new green infrastructure to improve air quality, reduce the heat island effect, and to control urban stormwater flows contributing pollution to its rivers and ultimately the Chesapeake Bay. Along with these standards, the city adopted a stormwater rule requiring new development to capture a majority of stormwater onsite through the use of nature-based tools like green roofs, rain gardens, constructed wetlands and improved tree canopies. To provide an incentive to exceed the minimum requirement of capturing 50% of stormwater onsite, the city created a Stormwater Retention Credit trading system, which allows landowners that exceed requirements to capture the value of the biophilic benefits by trading the exceedance as a credit to other landowners that are struggling to meet requirements. In this manner, the city is promoting a market that incentivizes nature-based solutions and increases the abundance of nature across the city’s landscape.

These legal mechanisms illustrate a flexible, adaptable approach. One that permits the planning and design of cities to evolve over time to embrace ecological solutions, which have utilitarian merit but also bring wonder to cities through the introduction of new nature-based amenities.

Another area of scholarship is the development of a growing library of biophilic indicators to help cities assess their progress towards their biophilic aspirations. The indicators are varied in focus and attempt to measure elements that are at the center of what it means to be a biophilic city. As a requisite of joining the Biophilic Cities Network as a partner city, we ask cities to develop a set of indicators that can be assessed and evaluated over time. Partner cities are asked to consider indicators in several broad categories that include the condition and abundance of nature in the city, the engagement of the city’s residents with nature, the pursuit of biophilic policies and governance, and human health/well-being indicators. In adherence to this network requirement, the partner cities are tracking an array of different parameters. Currently diverse, tracked indicators include progress toward overcoming inequitable or unfair distributions of urban nature, wildlife passage creation to enhance or restore connectivity, extent of biodiversity found within the city, and productive reuse of vacant land.

Mindful of Hopeful Urgency

The vision of biophilic cities represents a hopeful future for cities as places where the growing populations that call cities home have the opportunity to connect with and explore nature in the communities where they live and work on an everyday basis. We are mindful of the incredible challenges to this optimistic mindset, including the urgent need for solutions that address climate change and the expanding inequities for life’s most basic needs. We believe that access to nature is one such basic need because of the myriad of positive benefits that result. In natureful cities, we see the opportunity to create places where all residents have housing on streets with abundant access to healthy food and lifestyles, where children are safe and free to learn in the world around them, and where diverse economic opportunities exist that give back more than they take. This is an optimistic vision that we are pursuing at Biophilic Cities that we hope can be shared and can inspire.

Look Beyond the Headlines

By John McIlwain

“Only the contemplative mind has the ability to hold the reality of what is and the possibility of what could be.” -Richard Rohr

Reading the headlines these days is a sure way to experience fear and despair. This is especially true about climate change and the environment. After all, what good news is there when Scott Pruitt is finally forced out of the EPA only to be replaced by a coal lobbyist! Headline news like that offers little in the way of hope or optimism. So do we just give up, shrink back in despair, ignore what we read, and just go on with our lives?

The headlines, however, are not all the news. Dig behind them and you will find much that is positive. Here are a few recent examples:

Thanks to rapidly dropping costs for solar and wind power, REN21-The Renewable Energy Policy Network reports that in 2017, globally, “Solar photovoltaic (PV) capacity installations … add[ed] more net capacity than coal, natural gas and nuclear power combined.”

The New York Times reported on July 15, 2018, that:

“The average retail price of electricity in the United States is little changed from 2007, and, adjusted for inflation, prices are actually lower today. This comes as the power sector has reduced carbon dioxide emissions during that same period by 28 percent, according to the Energy Information Administration [E.I.A.].

Wind turbines supplied nearly 15 percent of [Texas’s] electricity last year, up from 2.2 percent in 2007, according to the E.I.A. … Over that time period, the state’s retail electric prices fell to 55 cents per kilowatt-hour, from 10.11 cents, before adjusting for broader inflation.”

Reuters reports:

“The Trump administration wants to…streamlin[e] permitting [for off-shore wind turbines] and carv[e] out vast areas off the coast for leasing – part of its ‘America First’ policy to boost domestic energy production and jobs.”

The ISO Newswire reports:

“On April 21, 2018, the lowest demand for electricity from the New England grid occurred in the middle of the day, not the middle of the night as is usual, due to the growth in solar PV panels tied to the grid.This was an historic first for New England. Meanwhile, California has been adding 2,000 megawatts of solar capacity in each of the past three years, and at one point in April 2017, 64 percent of all electric power on the California grid was solar or wind generated. Its grid is now struggling with how to manage periods of oversupply from solar and wind.”

Behind the grim headlines, the world is shifting. Yes, the process of weaning ourselves from carbon is imperfect, and too slow. That said, the shift is happening around the planet, driven by industry, national governments (except for the U.S.), and in the U.S. by state and local governments. Individual choices are driving it as well; from the cars we buy to the solar panels on our roofs, and even in what we consume each day.

So is the glass half full or half empty? The answer is “yes,” it’s both. That leaves it up to us to choose how we see the world.

We do need to honor our sense of fear and despair, and face them with courage and mindfulness in order not to be driven by them. Remember that underneath is the deep love we have for our planet, and our natural, heartfelt desire for the wellbeing of all life.

As Rohr says, it takes a contemplative mind to hold both “the reality of what is” and “the possibility of what could be,” namely a sustainable, renewable future. The future is not predetermined; it lies in our hands. It is a more powerful choice to see the glass half full despite the headlines, to chose to focus on the broader reality of the changes occurring around us. Optimism is often a choice that requires courage, but living with a sense of possibility for the future brings aliveness and can propel us into positive action, something despair never can.

John McIlwain is an advisor to the Garrison Institute’s Climate, Mind and Behavior program.

Photo by Elijah O’Donell on Unsplash.

Entrepreneurs Who Design Generously: Celebrating Nature-Inspired Innovation With the Ray of Hope Prize

Photo: Team Nexloop accepts the 2017 Ray of Hope Prize at Bioneers, presented by the Ray C. Anderson Foundation. Left to right: John Lanier, Executive Director, Ray C. Anderson Foundation; C. Mike Lindsey, Anamarija Frankic, Jacob Russo, all from NexLoop; Beth Rattner, Executive Director, Biomimicry Institute.

These aren’t your everyday entrepreneurs. They understand that truly groundbreaking climate change solutions won’t come from the same take, make, and waste mindsets that have gotten us into our current environmental messes. Instead, they seek to emulate the natural world to create solutions that are regenerative, circular, and generous to all species on this planet.

The Biomimicry Launchpad supports this new kind of entrepreneur. Created by the Biomimicry Institute and sponsored by the Ray C. Anderson Foundation, it’s the world’s only accelerator program that focuses on helping early-stage entrepreneurs bring biomimetic, or nature-inspired, innovations to market. Each year, Launchpad teams are eligible to compete for the Ray C. Anderson Foundation’s $100,000 Ray of Hope Prize®. Teams are invited to join the Launchpad either by applying directly, or by participating in the Biomimicry Global Design Challenge, a global competition for university students and professionals to create nature-inspired climate change solutions.

Bioneers celebrates these bold thinkers by presenting the Ray of Hope Prize each year on the mainstage. Sure, it’s a competition, but year after year, these teams form deep bonds, and many go on to collaborate on whole-systems solutions. It’s a great example of how Bioneers fosters connection, collaboration, and community.

Launchpad teams have gone on to win awards and additional funding, appear at conferences all over the world, and participate in other accelerator and incubator programs. Read on to learn more about these teams and what they’ve accomplished in their post-Bioneers journeys:

Collaborating to showcase nature-inspired, closed-loop water systems

Two Biomimicry Launchpad alumni teams are part of a consortium that has won a €10 million grant from the European Union to that aims to demonstrate and test innovations that close water loops, feed the soil, and promote local economies.

As part of the HYDROUSA grant, the Mangrove Still design, a desalinating still inspired by mangrove ecosystems, and the BIOCultivator, a growing/composting system inspired by lizards, will be included in a pilot project on Greek islands. This wide-scale grant project will incorporate different nature-inspired solutions to create a regenerative system that will produce fresh water for agricultural and household use, plus create jobs in the region. The Mangrove Still system will be used to produce freshwater for a greenhouse, and the BIOCultivator design will be adapted into a compost cultivator that will be used to fertilize and irrigate soil.

Alchemia Nova CEO Johannes Kisser is leading up the development of the biomimicry applications in the grant, along with Regina Rowland and the team at Bioversum, a new NGO that develops projects that apply the principles of biomimicry and circular economy and design.

Teaming up to collaborate on food system solutions

The 2016 Ray of Hope Prize-winning team, LifePatch (formerly BioNurse) is collaborating with the Mangrove Still team (described above) to develop a joint project that utilizes both of their designs to address both water and soil issues resulting from climate change. By combining the Mangrove Still’s affordable and efficient desalination design with LifePatch’s biodegradable, low-cost way to restore degraded soil, they aim to create a whole-systems approach to helping agricultural communities suffering from water scarcity and desiccated soil. The Mangrove Still team was previously awarded a grant from Dubai Expo 2020 and used those funds to test their system in Egypt, India, Namibia, Cape Verde, and Cyprus. Both of these teams are jointly applying for funds to test their combined technologies.

Prototyping a resilient water management system, inspired by nature

Team NexLoop won the 2017 Ray of Hope Prize for their water management system for urban food producers, inspired by the way living systems capture, store, and distribute water. Since their win, they have spoken at conferences around the world, including the National Science Festival in Croatia, and are focusing on developing a field-ready prototype. They have identified four international pilot sites and have been actively applying for additional funding to carry out these pilots.

Accelerating an indoor farming system

Team Hexagro created a modular growing system that enables people to grow fresh food in indoor settings. Since their Launchpad experience, they’ve displayed their designs at conferences all over the world, including at a technology display in Lyon, Milan Design Week, Seeds and Chips in Milan, Tech Open Air in Berlin, and at universities in Costa Rica and Slovenia. They’ve also participated in multiple startup pitch events, bootcamps and incubators, including the Katana Bootcamp in Stuttgart, Germany, where they were selected as the #1 pitch out of 100 teams participating in the bootcamp, the Kickstart Accelerator program in Switzerland, and the Lee Kuan Yew Global Business Plan competition in Singapore. Most recently, the Hexagro team was accepted to Singularity University’s SU Ventures accelerator program.

Don’t miss out! Six new international Biomimicry Launchpad teams will be coming to Bioneers this year to showcase their nature-inspired climate change solutions. You can find out who the next 2018 Ray of Hope Prize winner is and meet all of the 2017-18 teams on Saturday, October 20th. Learn more about the Biomimicry Global Design Challenge here and the Biomimicry Launchpad here.

In Memory of Ralph Paige: Champion of Black Farmers

As I walked toward the meeting hall crowded with farmers, I could hear a buzz of joyful collegiality. I opened the swinging door and took a step inside and instantly the room fell silent. As the only white person in a group of about 200 Black farmers in Alabama, I got a small fleeting taste of what it means to be other. Uncomfortable and self-conscious, I froze in awkward pause.

Ralph Paige, a man of sizable physical stature, lifted his head, looked around and with a smile on his face said, “Who let the white folks in?” Everyone, including me, cracked up. The laughter pushed the silence aside and the tension dissipated. The group fell back into jovial conversation and I entered feeling relieved by the unconventional welcome.

That was Ralph. He knew full well the realities of racial distrust, but it didn’t prevent him from bringing people together to work for justice and to improve people’s lives.

When I first met Ralph, about 20 years ago, he was the Executive Director of the Federation of Southern Cooperatives (FSC) and was a Bioneers board member at the time. As the Project Manager for the Bioneers Restorative Development Initiative, I was organizing some of the first organic farming and medicinal herb trainings in the Deep South for FSC farmers.

The FSC grew out of the civil rights movement in the 1960’s to support Black farmers and help them retain land ownership. According to the 1910 Census of Agriculture, Black farmers numbered over 200,000. By the year 2001, those numbers were estimated to have shrunk to 19,000.

In a 1992 New York times article, Douglas Bachtel of the University of Georgia said, “Farm declines seemed to have plateaued for whites in the last decade or so, but black farmers are on their way to extinction.”

As a testament to the work of the FSC under Ralph Paige’s leadership, the population of Black farmer’s rose to 33,371 in 2012.

Hard fought victories came despite the fact that the FSC was the target of institutional discrimination. In the early days of the FSC as Black voter registrations increased in counties where they organized farmer co-ops, the FBI inexplicably raided their office and confiscated all their files. After a lengthy delay, they were returned without any explanation.

In 1992, Ralph and the FSC led a caravan of Black farmers to Washington DC to protest the discriminatory practices of the USDA. In 1997, the FSC helped provide legal assistance to Black farmers to join the class action suit, Pigford v. Glickman, against the USDA. The successful lawsuit awarded $2 billion to 15,000 claimants–the largest civil right judgment in the history of the United States. Lead attorney for the class action suit, J.L Chestnut, said, in a Bioneers keynote presentation, that up to that point, no one had ever heard the words Black farmer and billions of dollars in the same sentence.

When tragedy struck in the form of hurricanes Katrina and Rita, Ralph garnered the cooperative power of the FSC to aid thousands of farmers, fishers and families who suffered loss of home, loved ones and livelihoods.

A life-long civil rights warrior, Ralph Paige died of congestive heart failure on June 28. He worked tirelessly, at the expense of his own health, to help Black farmers be accorded the same opportunities as anyone else. His work invigorated rural southern communities culturally and economically. Ralph was a politically savvy operator with a big heart.

His legacy is apparent in the 200 units of low income housing, the 18 community credit unions, the 75 farmer cooperatives and the award-winning rural training center that the FSC built under Ralph Paige’s 30-year leadership, despite the roadblocks of discrimination and the racially rigged system that he helped break a few holes in.

Putting Carbon at the Center of Agricultural Policy

Excerpted from an Interview with Calla Rose Ostrander

Calla Rose Ostrander is an environmental consultant to the Marin Carbon Project, and formerly Climate Change Coordinator for the city of Aspen and Climate Change Project Manager for San Francisco.

When I was the Climate Change Project Manager for the City of San Francisco, John Wick gave a presentation in the Office of the Department of Environment on how the Marin Carbon Project (which John co-founded) was working to promote farming practices that draw carbon from the atmosphere and capture it in the soil. He shared his rigorous peer-reviewed published papers and a carbon-offset protocol that he had created around the concept of soil carbon sequestration. It included a whole methodology for farming that fit into the existing USDA infrastructure. I had never seen anybody do their homework quite like that. He had designed the pieces to transition the entire agricultural system. The research and trials had been done and he had found the framework in which to embed it into the agricultural system: the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service and California’s Resource Conservation Districts.

That meeting led to an invitation to work with the Carbon Cycle Institute. They had a system, they did the science, they involved the right government institutions and the right stakeholders, and were supporting the farmers. There was an ecosystem of organizations and individuals to help scale it up. I was able to come in and help take all of that out to the broader landscape.

Levers of Power: Economy, Infrastructure, Funding and Storytelling

My background is international political economy, which is how you understand the levers of modern Western society, how politics intersect with economics, and how culture, religion or science – or whatever your basis is – shapes politics. As a political economist, my job is to assess things like the need for a market policy to drive organic materials out of landfills and out of dairy ponds and into compost.

When we burn carbon, we create energy. When we eat carbon, we get energy. When we put carbon in compost and spread it on the soil, it gives energy to the system. Carbon is the physicalized way that we share energy on the planet.

The challenge is that the current economic framework doesn’t recognize the exchange of energy as inherently valuable. When exchanged in a positive way, there is an abundance of carbon within the terrestrial system. It challenges the idea that the scarcity of carbon is what creates its value. Carbon is one of the most abundant elements on the planet and is what life is built on–that is the basis of its value.

We’re not going to change the economic paradigm tomorrow, but we are trying to look at all the ways in which our socio-political and market-based culture creates value, and then help shape it so we can begin to move that energy exchange in a positive abundant direction instead of in a single direction–into the atmosphere. Carbon is an untapped resource that can be actively harnessed if humans take a responsible role in the carbon cycle.

To affect policy change, consistency is needed across the scientific models between the State of California and the USDA, which requires additional research. Once we get consistency, the state and the feds are going to accept the models and then programs can be brought online.

In order to get funding passed, we need legislators from Southern California because the leaders of our California government are primarily based in Los Angeles. I moved there to understand who the constituency is, what they care about, how we engage them, how the idea of Carbon Farming and carbon sequestration brings value to them, and then how to mobilize them to tell their representatives that it is important.

How we, as a movement, communicate to the outside world needs to be cohesive. Kiss the Ground wanted to make a movie about soil and climate change. We needed to make sure that that first story animation said the things that everybody in the movement agreed on, that we got the science right, that we didn’t overstep it, that we said things that everybody from my scientist to my advocates and my politicians could agree with. Once we’re all saying the same thing, we then have shared values and the language needs to communicate that. Working with Kiss the Ground to write the movie created vocabulary cohesion, and therefore helped to align political and social will, which is crucial to take the body of work to scale.

The Framework: Carbon Farm Plans

The model that the Marin Carbon Project developed is to build Carbon Farming into Conservation Agriculture. USDA Conservation Agriculture Programs have been around since the post-Dust Bowl era within the Natural Resources Conservation Service, which created Conservation Districts across the country.

The Marin Carbon Project and The Carbon Cycle Institute looked at all the practices currently in Conservation Agriculture that focus on carbon and enhancing terrestrial or soil carbon. Instead of a Conservation Plan they created a Carbon Farm Plan that puts carbon at the center, because when you manage for carbon, you manage for water, you manage for nutrients, you manage for productivity and energy. That’s why it is a replicable model.

There are approximately 33 Resource Conservation Districts (RCD) in the State of California that have Carbon Farm Planning programs, meaning a rancher or farmer could go to their RCD and get assistance designing a carbon farming plan. Having a Carbon Farm Plan makes farmers and ranchers eligible for existing subsidies through the USDA Resource Conservation Service as well as California’s Healthy Soils Initiative.

Most agricultural soil systems are highly degraded and impacted and are facing challenges from extreme weather. Ranchers or rangeland managers don’t have a lot of capital. These are systems that operate on very small margins and they’re challenged by increasing land prices. They stay on the land by working it.

Even though a one-time application of compost is like magical medicine for the soil, compost is expensive and we’re going to need a lot more of it. The price needs to come down on one side for the rancher, but probably needs to go up for the producer to be profitable. Subsidies and more ways of farmers producing their compost on farm are needed.

To be successful means getting enough carbon back in that soil system so that it can be highly productive, and that’s not just compost. There are 34 practices “officially” approved by USDA and there are hundreds of other conservation practices for natural resource conservation and improving soil health. Those that specifically increase soil carbon sequestration are the ones that we put together into the Carbon Farming Plan. Colorado State University (a key partner in the development of the EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Inventory protocols) and the USDA are using the tool that we created for California, the COMET-Planner, which evaluates potential carbon sequestration and greenhouse gas reductions by adopting NRCS conservation practices. It’s also being applied internationally.

Next Steps: What’s Needed?

A lot of farmers and ranchers are already doing many of these practices. They need monetary and technical support to manage for carbon on their properties.

In addition to government subsidies, private sector investment is needed. Local infrastructure is really important for supply chain development and keeping the value closer to the farmer. Right now, most of the wool that’s produced in California–even though it’s some of the highest-grade quality–gets thrown away because there’s no way to bring it to market. You have to send it to Texas or China to get washed and then there is the problem of where to send it once it’s washed to get spun or milled, and how to make the fabric. What we’re doing now is looking at how we can support a manufacturing infrastructure around local fiber systems that are climate beneficial, because that’s going to bring a value back to the farmer or rancher and value to the soil by building organic matter.

Fibershed founder, Rebecca Burgess, has built a community in California of over 140 small to mid-scale producers and is working with North Face by producing value-added products with wool that was produced in a climate-beneficial manner using Carbon Farming practices. We’re looking at what is it that those local producers need in order to successfully make these practices happen on their operations.

There are wonderful organizations that we’ve partnered with – CAFF, CalCAN, Californians Against Waste – who are doing advocacy. What was missing was the smaller, mid-scale producer voice at the table. We are helping those types of producers organize and have their own lobbyists because in order to get government money, you have to show up at every meeting and every hearing, and go to the offices and talk to all the people. That’s how policy gets made, that’s how money gets distributed. You’ve have to know who your legislators are and talk to them. John Wick is currently funding a project to connect the small-scale Northern California climate beneficial producers to a lobbying group that can represent them so that they can have a voice at the table.

There’s a framework, there are funding streams, and now it’s a question of listening to people who are already doing this work as well as those who are interested. What do they need to continue or what they need to do more of it? A model is in place that can live on its own within existing infrastructure. New resources like education and more funding can be funneled towards that infrastructure. There are structural things that still need to be changed, but the model is active, right now, on the agriculture landscape in California.