Can animals feel? Do they empathize? Do they experience sadness? The more we come to understand the natural world, the more compelling the argument for profound animal consciousness becomes.

Human beings, throughout history, have placed themselves in a superior class—one that stands alone at the top of a complex web of Earthly life. Though we know that, by definition, we are animals, we’ve become rather used to distinguishing ourselves from the rest of that web. This manufactured divide allows us to assume that what is “animal” is not “human.” But what if the differences between the brains of humans and those of much of the rest of the animal kingdom are far less distinct than we once assumed? While humans are capable of incredibly complex thought patterns and emotions, writer and conservationist Carl Safina suggests that the historic practice of using humans as a measuring stick by which to diagnose “consciousness” may be flawed.

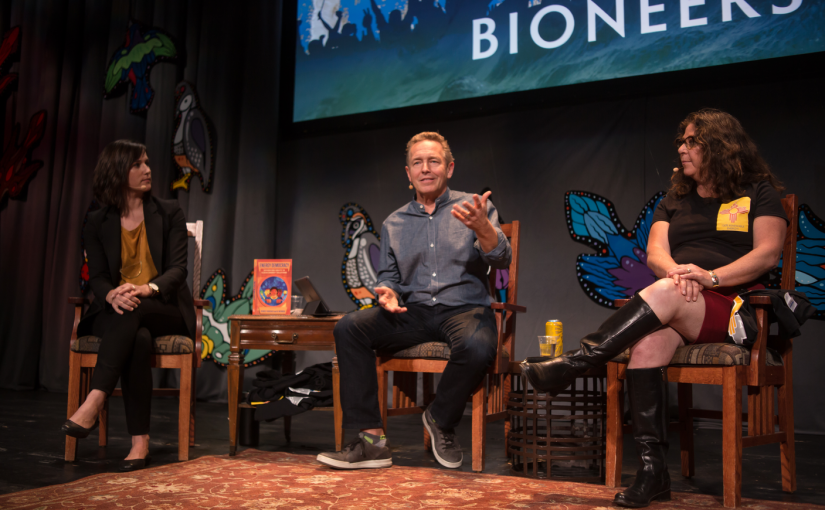

Explorations of animal and plant intelligence and consciousness have been a part of the Bioneers Conference for decades, and as the research piles up, popular interest continues to grow. We were stunned when a recent Bioneers video on the topic exploded online, now at well over two million views.

In his book Beyond Words (Picador, 2016), Safina describes evidence of radical animal consciousness in elephants, octopuses, honeybees … even worms. The following is an excerpt from the book’s chapter “The Same Basic Brain.”

We’re overjoyed to be hosting Carl Safina at the 2017 Bioneers conference to discuss animal consciousness and lessons from the natural world.

Four rounded babies are following their massive mothers across a broad, sweet-smelling grassland. The adults, striding with deliberate purpose as though keeping an appointment, are nodding toward the wide, wet marsh where about a hundred of their compatriots are mingling. Families commute daily between sleeping areas in brush-thicketed hills and the marshes. For many it’s ten miles (fifteen kilometers) round-trip. Between here and there and sun to sun, a lot can happen.

Our job: travel around in the morning, finding them as they’re coming in; see who’s where. The idea is simple, but there are dozens of families, hundreds of elephants.

“You have to know everyone. Yes!,” Katito Sayialel is saying. Her lilting accent is as clear and light as this African morning. A native Maasai, tall and capable, Katito has been studying free-living elephants with Cynthia Moss for more than two decades.

How many is “everyone”?

“I can recognize all the adult females. So,” Katito considers, “nine hundred to one thousand. Say nine hundred. Yes.”

Recognizing hundreds and hundreds of elephants on sight? How is this possible? Some she knows by marks: the position of a hole in an ear, for instance. But many, she just glances at. They’re that familiar, like your friends are.

When they’re all mingling, you can’t afford to say, “Wait a minute; who was that?” Elephants themselves recognize hundreds of individuals. They live in vast social networks of families and friendships. That’s why they’re famous for their memory. They certainly recognize Katito.

“When I first arrived here,” Katito recalls, “they heard my voice and knew I was a new person. They came to smell me. Now they know me.”

Vicki Fishlock is here, too. A blue-eyed Brit in her early thirties, Vicki studied gorillas and elephants in the Republic of the Congo before bringing her doctoral diploma here to work with Cynthia. She’s been here for a couple of years and has no plans to go anywhere else if she can help it. Usually Katito takes attendance and rolls on. Vicki stays and watches behavior. Today we’re out on a bit of a jaunt; they’re kindly orienting me.

Just outside the high “elephant grass,” five adults and their four young babies are selecting a shorter and far less abundant grass. It’s more work; it must taste better. They haven’t read a treatise on the nutritional content of grass. In a sense, their subconscious tells them what to do by rewarding them with pleasure for making the richer choice. It works the same for us—that’s why sugar and fat taste so good.

The grazing elephants trail a train of egrets and an orbiting galaxy of swirling swallows. The birds rely on elephants to stir up insects as, like great gray ships, they plow through the grassy sea. Light shifts on their wide, rolling backs like sun on ocean waves. Sounds of ripping, chewing. Flap of ear. Plop of dung. The buzz of flies and swoosh of swatting tails. Soft tom-tom footfalls. And, mostly, the quiet ways of ample beasts. Wordlessly they speak of a time before human breath. They get on with their lives, ignoring us.

“They’re not ignoring us,” Vicki corrects. “They have an expectation of politeness, and we’re fulfilling it. So they’re not paying us any mind.

“They weren’t always like this to me,” she adds. “When I started, they were used to vehicles snapping a few pictures and moving along. They were not wildly happy about me just sitting and watching them for long periods. They expect you to behave a certain way. If you don’t, they will let you know that they notice. Not in a threatening way. You might get a head shake and a look like, ‘What’s your problem?’ ”

Through hummocks and the bush, in our vehicle we amble with them. An elephant named Tecla, walking just a few yards ahead to our right, suddenly turns, trumpets, and generally objects to us. To our left , a young elephant wheels and screams.

“Sorry, sorry, sorry,” Katito says to Tecla. She brakes to a stop, turning off the ignition. It appears to me that we have separated this mother from her baby. But Tecla is not the mother. Another female, whose two breasts are full of milk, runs over, cutting just in front of us. This one is actually the mother. Basically Tecla was communicating, “The humans are getting between you and your baby; come and do something.”

“Elephants, they are like human beings,” offers Katito. “Very intelligent. I like their characters. I like the way they behave and hold their family, the way they protect. Yes.”

Like human beings? In some fundamental ways we seem—we are—so similar. But I can see Cynthia wagging a finger of caution, reminding me that elephants are not us; they are themselves.

Mother rejoins baby, restoring order. We slowly proceed. When one individual knows another’s relationship to a third—as Tecla knows who the baby’s mother is—it’s called “understanding third-party relationships.” Primates understand third-party relationships too, and so do wolves, hyenas, dolphins, birds of the crow family, at least some parrots. A parrot, say, can act jealous of its keeper’s spouse. When the vervet monkeys that are common around camp hear an infant’s distress call, they instantly look to the infant’s mother. They know exactly who they and everyone else are. They understand precisely who is important to whom. When free-living dolphin mothers want young ones to stop interacting with humans, the mothers sometimes direct a tail slap at the human who has the baby’s attention, signaling, in effect, “End the game; I need my child’s attention.” When the dawdling youngsters are interacting with dolphin researcher Denise Herzing’s graduate assistants, their mothers occasionally direct these—what could we call them: reprimands?—at Herzing herself. This shows that the dolphins understand that Dr. Herzing is the leader of all the humans in the water. For free-living creatures to perceive rank order in humans—just astonishing.

“What I find most amazing about it,” Vicki sums up, “is that we can understand each other. We learn the elephants’ invisible boundaries. We can sense when it’s time to say, ‘I don’t want to push her.’ Words like ‘irritated,’ ‘happy’ or ‘sad’ or ‘tense’—they really do capture what that elephant is experiencing. We have a shared experience because,” she adds with a twinkle, “we’ve all got the same basic brain.” \

I look at these elephants, so relaxed about us that they’re passing within a couple of paces of our vehicle. Vicki says, “This is one of the greatest privileges, moving along with elephants who are okay with you being here. These guys all go into Tanzania, where there are poachers everywhere. But here—.” Vicki talks to them in soothing tones, saying, “Hello, darling” and “Aren’t you a sweet girl.” Vicki recalls that after the famed Echo’s death, her family went away for three months under the leadership of Echo’s daughter Enid. “And when they returned, I started saying things like ‘Hello, I missed you—’ And suddenly Enid’s head swept up, and she gave this huge rumble; her ears were flapping and they all came around, close enough that I could have touched them, and the glands on all their faces were streaming with emotion. That’s trust. I felt as though,” Vicki says fondly, “I was getting an elephant hug.”

Once, I was watching elephants with another scientist in another African reserve. Several adult elephants were resting with their young in the shade of a palm, fanning their ears in the heat. The scientist opined that the elephants we were watching “might simply be moving to and away from heat gradients, without experiencing anything at all.” He declared,“I have no way of knowing whether that elephant is any more conscious than this bush.”

No way of knowing? For starters, a bush behaves quite differently from an elephant. The bush shows no sign of having a mental experience, of showing emotions, of making decisions, of protecting its offspring. On the other hand, humans and elephants have nearly identical nervous and hormonal systems, senses, milk for our babies; we both show fear and aggression appropriate to the moment. Insisting that an elephant might be no more conscious than a bush isn’t a better explanation for the elephants’ behavior than concluding that an elephant is aware of what’s going on around it. My colleague thought he was being an objective scientist. Quite the opposite; he was forcing himself to ignore the evidence. That’s not scientific—at all. Science is about evidence.

At issue, here, is: Who are we here with? What kinds of minds populate this world?

This is hazardous terrain. We won’t assume that other animals are or aren’t conscious. We’ll look at evidence and go where it leads. It’s too easy to assume wrongly, then carry those assumptions around for, say, centuries.

In the fifth century b.c.e., the Greek philosopher Protagoras pronounced, “Man is the measure of all things.” In other words, we feel entitled to ask the world, “What good are you?” We assume that we are the world’s standard, that all things should be compared to us. Such an assumption makes us overlook a lot. Abilities said to “make us human”—empathy, communication, grief, toolmaking, and so on—all exist to varying degrees among other minds sharing the world with us. Animals with backbones (fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals) all share the same basic skeleton, organs, nervous systems, hormones, and behaviors. Just as different models of automobiles each have an engine, drivetrain, four wheels, doors, and seats, we differ mainly in terms of our outside contours and a few internal tweaks. But like naïve car buyers, most people see only animals’ varied exteriors.

We say “humans and animals” as though life falls into just two categories: us and all of them. Yet we’ve trained elephants to haul logs from forests; in laboratories we’ve run rats through mazes to study learning, let pigeons tap targets to teach us Psychology 101; we study flies to learn how our DNA works, give monkeys infectious diseases to develop cures for humans; in our homes and cities, dogs have become the guiding protectors for humans who see only by the light of their four-legged companions’ eyes. Throughout all this intimacy, we maintain a certain insecure insistence that “animals” are not like us—though we are animals. Could any relationship be more fundamentally miscomprehended?

To understand elephants we must delve into topics like consciousness, awareness, intelligence, and emotion. When we do, we realize with dismay that there aren’t standard definitions. The same words mean different things. Philosophers, psychologists, ecologists, and neurologists are the blind men all feeling and describing different parts of the same proverbial elephant. But, silver lining: their lack of agreement frees us to walk out of the academic bar brawls into clearer air and a wider view, and do a little of our own thinking.

So let’s start by defining consciousness. The standard we’ll use is: Consciousness is the thing that feels like something. That simple definition comes from Christof Koch, who heads the Allen Institute for Brain Science, in Seattle. Cut your leg, that’s physical. If the cut hurts, you’re conscious. The part of you that knows that the cut hurts, that feels and thinks, is your mind. Relatedly, the ability to feel sensations is called sentience. The sentience of humans, elephants, beetles, clams, jellyfish, and trees ranges on a sliding scale, from complex in people to seemingly none in plants. Cognition refers to the capacity to perceive and acquire knowledge and understanding. Thought is the process of considering something that’s been perceived. Like everything about living things, thought also happens on a wide-ranging sliding scale; thinking can take the form of a jaguar assessing how to approach a wary peccary from directly behind, an archer aiming at a target, or a person considering a proposal of marriage. Sentience, cognition, and thinking are overlapping, processes of conscious minds.

Consciousness is a bit overrated. Heartbeat, breathing, digestion, metabolism, immune responses, healing of cuts and fractures, internal timers, sexual cycling, pregnancy, growth—all function without consciousness. Under general anesthesia we remain very much alive though not conscious. And during sleep our unconscious brains are working hard, cleansing, sorting, rejuvenating. Your body is run by a competent staff that’s been on the job since before the company acquired consciousness. Too bad you can’t personally meet your team.

We might imagine consciousness as the computer screen we see and interact with, one run by software codes that we can’t detect and don’t have a clue about. Most of the brain runs in the dark. As science author and former Rolling Stone magazine editor Tim Ferris wrote, “One’s mind neither controls nor comprehends most of what’s going on in one’s brain.”

Why be conscious at all? Trees and jellyfish do just fine, yet may not experience sensations. Consciousness seems necessary when we must judge things, plan, and make decisions.

How does consciousness—elephant, human, whatever—arise in the mush of our physical cells and the mesh of their electrical and chemical impulses? How does a brain create a mind? No one knows how nerve cells, also called neurons, create consciousness. What we know: consciousness can be affected by brain damage. So consciousness does happen in the brain. As Nobel Prize–winning mind-brain scientist Eric R. Kandel wrote in 2013, “Our mind is a set of operations carried out by our brain.” Consciousness seems to somehow result from, and depend on, neurons networking.

How many networked neurons are needed? No one knows where the most rudimentary consciousness lurks. Jellyfish, probably not conscious; worms, maybe so. With about one million brain cells, honeybees recognize patterns, scents, and colors in flowers and remember their locations. The bees’ “waggle dance” communicates to their fellow hivemates the direction, distance, and richness of nectar they’ve found. Bees “show superb expertise,” says famed neurologist Oliver Sacks. Honeybees will interrupt a colleague’s waggle dance if they’ve experienced trouble at the same flower source, such as a brush with a predator like a spider. Honeybees subjected by researchers to simulated attack show, said researchers, “the same hallmarks of negative emotions that we find in humans.” Even more intriguingly, honeybee brains contain the same “thrill-seeker” hormones that in human brains drive some people to consistently seek novelty. If those hormones do deliver some tingle of pleasure or motivation to the bees, it means bees are conscious. Certain highly social wasps can recognize individuals by their faces, something previously believed the sole domain of a few elite mammals. “It is increasingly evident,” says Sacks, “that insects can remember, learn, think, and communicate in quite rich and unexpected ways.”

Can elephants, insects, or any other creature really be conscious without the big wrinkly cerebral cortex where human thinking happens? Turns out, yes; even humans can be. A thirty-year-old man named Roger lost about 95 percent of his cortex to a brain infection. Roger can’t remember the decade before the infection, can’t taste or smell, and has great difficulty forming new memories. Yet he knows who he is, recognizes himself in a mirror and in photographs, and generally acts normal around people. He can use humor and can feel embarrassed. All with a brain that does not resemble a human brain.

The common human notion that humans alone experience consciousness is backward. Human senses have evidently dulled during civilization. Many animals are superhumanly alert—just watch these elephants when anything changes—their detection equipment exquisitely tuned for the merest crackle of danger or whiff of opportunity. In 2012, scientists drafting the Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness concluded that “all mammals and birds, and many other creatures, including octopuses,” have nervous systems capable of consciousness. (Octopuses use tools and solve problems as skillfully as do most apes—and they’re mollusks.) Science is confirming the obvious: other animals hear, see, and smell with their ears, eyes, and noses; are frightened when they have reason for fright and feel happy when they appear happy.

As Christof Koch writes, “Whatever consciousness is . . . dogs, birds, and legions of other species have it. . . . They, too, experience life.”

My dog Jude was sleeping on the rug, dreaming of running, his wrists flicking, when he let out a long, eerily muffled howl. Chula, my other dog, instantly piqued, trotted over to Jude. Jude startled awake and leapt to his feet barking loudly, just as a person wakes from a night terror with a vivid image and a scream, taking a few moments to get oriented.

Each line we attempt to draw crisply, as between elephants and humans, nature has already blurred with the smudgy brush of deep relation. But what about living things with no nervous system? That is a dividing line. Isn’t it?

With no apparent nervous system, plants make the same chemicals—such as serotonin, dopamine, and glutamate—that serve as neurotransmitters and help create mood in animals, including humans. And plants have signaling systems that work basically as do animals’, though slower. Michael Pollan observes, a bit metaphorically, that “plants speak in a chemical vocabulary we can’t directly perceive or comprehend.” That’s not to say that plants experience sensations, necessarily, but they do some intriguing things. We detect chemicals by smell and taste; plants sense and respond to chemicals in air, soil, and on themselves. Plants’ leaves turn to track the sun. Growing roots approaching an obstacle or toxin sometimes alter course prior to contact. Plants have reportedly responded to the recorded sound of a munching caterpillar by producing defensive chemicals. Plants attacked by insects and herbivores emit “distress” chemicals, causing adjacent leaves and neighboring plants to mount chemical defenses, and alerting insect-killing wasps to move in, blunting the attack. Flowers are plants’ way of telling bees and other pollinators that nectar is ready.

But except for insectivorous and sensitive-leaved plants, most plants behave too slowly for the human eye. Gazing across a meadow, Pollan wrote, he “found it difficult to imagine the invisible chemical chatter, including the calls of distress, going on all around—or that these motionless plants were engaged in any kind of ‘behavior’ at all.” Yet Charles Darwin concluded his book The Power of Movement in Plants by noting, “It is hardly an exaggeration to say that the tip of the radicle [root] . . . acts like the brain of one of the lower animals . . . receiving impression from the sense organs and directing the several movements.” Granted, we are treading into a vast minefield of potential misinterpretation. Like Cynthia Moss with elephants, the late botanist Tim Plowman, wasn’t interested in comparing plants to people. He appreciated them as plants. “They can eat light,” he said. “Isn’t that enough?”

My main reason for getting into the weeds here is to realize that, compared to the strangeness of plants and the large differences between plants and animals, an elephant nursing her baby is so like us that she might as well be my sister.

This excerpt on has been reprinted with permission from Beyond Words by Carl Safina, published by Picador, 2016. Catch Safina speaking on animal consciousness and lessons from the natural world at the 2017 Bioneers Conference.