Indigenous Peoples were the original stewards of the land, but efforts to recognize ancestral territories are often buried under years of colonization and urban development. The State of California is looking to change that.

In this conversation, two Indigenous women on the frontlines of systems change discuss the meaning behind an Indigenous land acknowledgment bill tha was introduced to the California legislature in May 2020. Featuring Alexis Bunten (Unangan/Yup’ik), the Bioneers Indigeneity Program co-director, and Dr. Joely Proudfit (Luiseño), the director of the California Indian Culture and Sovereignty Center at Cal State San Marcos.

ALEXIS: California Assembly Member James Ramos introduced this new bill — Assembly Bill 68 — to the State of California. It encourages public schools, parks, libraries, and museums to adopt land acknowledgement processes that recognize Native American tribes as traditional stewards of the land on which an entity is located.

Can you explain what land acknowledgement is? And why is it important?

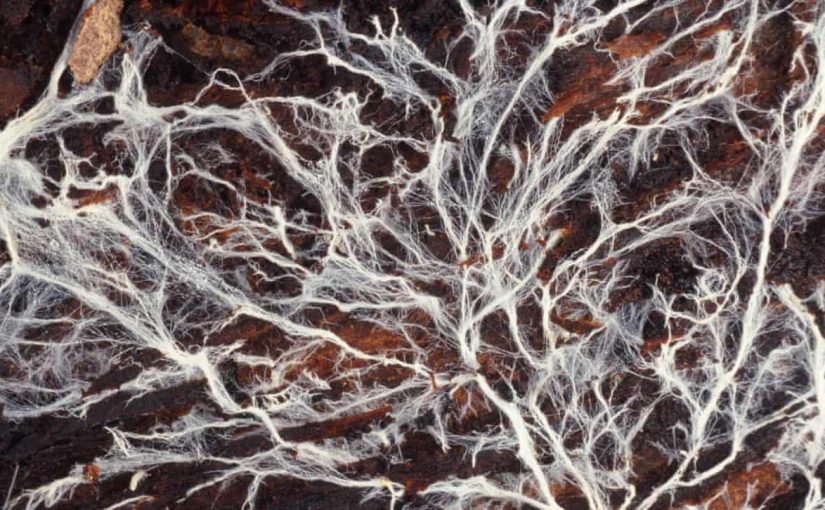

JOELY: Land acknowledgement is a formal statement that recognizes and respects the Indigenous People of the territories that one is on. This addresses that enduring relationships exist between the original peoples of the land who have always maintained the land, who have preserved the land, and who still are part of the land. It also allows for others to provide an active conciliation with those peoples whose land they are currently working or living on.

ALEXIS: Is it important for everybody to know whose land they’re on?

JOELY: I think California Indians have been so erased in every capacity, from schools and curriculum to our parks and murals. I see land acknowledgement as a way to share our culture, our history, our present, and our future with everyone who lives in the state. This is a beautiful opportunity to provide a relationship and expression of gratitude for people who have become settlers to this land. We want them to remove themselves as settlers and be perceived as guests.

ALEXIS: Yes! And a lot of people don’t seem to realize that California Indians are here in every major region. The descendants of the original populations, which were here when Spanish settlers arrived, are still here.

JOELY: Exactly. Land acknowledgements don’t exist in past tense. They exist out of the historical context; it’s important that they invite people to learn and build relationships with other people. For example, my daughter goes to a public school in the city of Carlsbad, which would be considered on Luiseño and Kumeyaay lands. I would love for her school to make a statement before or after they do the Pledge of Allegiance, so that all those young people can realize whose land they’re on.

It could be something as simple as just saying the words out loud: We acknowledge and we thank the original inhabitants who have occupied, maintained, secured this place, and who still exist. That’s such a powerful statement.

ALEXIS: I love the idea of adding it to the Pledge of Allegiance. Are there any other states that have a policy like this one in place yet?

JOELY: We will be the first. California is a very progressive state, so hopefully we’ll lead the charge.

I also want to remind people that they’re living in a place that was fraught with colonialism, and remind them of the fact that California Indian people are still here and thriving in the face of a brutal history. We’re not trying to tell anybody they have to go back to where they came from. We simply want them to acknowledge and to share this space with us, and to respect the environment and the ecology that exists here.

ALEXIS: Just last year, our governor has formally acknowledged that California Indians did experience a genocide, and there have been a lot of people and allies who agree that it’s happened. There’s no reason that we shouldn’t acknowledge what happened in California with the same strength and vigor that we remember other genocides that have taken place in history.

JOELY: Right. It’s a struggle to maintain and keep our lands, it’s a struggle to maintain fresh water and our water resources. So acknowledging the land is a transformative act that works to undo intentional erasure of Indigenous Peoples. It’s the first step in decolonizing land relations, and ultimately provides a learning opportunity for individuals who may never have heard the names of the tribes on whose land that they reside on, or play on, or visit. We need to do even more

I’m grateful for Governor Newsom’s apology, but I do think we need to do more, and if I had my way, we’d overhaul the curriculum and invest lots of money in doing that in our public K–12, but also in our university systems. Recognizing and doing a land acknowledgement doesn’t cost anything. You can do this act, and gratitude, and kindness, and education, and appreciation at no cost, but the dividends that I think it pays forward are immeasurable.

ALEXIS: I agree. So what can people do to support Assembly Bill 68. Does it have to be only citizens of California? And what do we need to do?

JOELY: I’d like for anyone and everyone, including organizations, to write a letter of support to the California State Assembly. A good old-fashioned letter goes a really long way in this endeavor. I can’t imagine anyone being opposed to this, as it’s a really wonderful way to say “thank you” to the Indigenous Peoples of California. If you’re not Indigenous to the place that you’re on, you can choose to be a settler or you can choose to be a guest. And I’m of the belief that people want to choose to be a guest.

ALEXIS: Right. And I think you raise the point that this is an issue of human decency and humanity in doing what’s right, and that it’s absolutely not a partisan issue. If we love the oceans, the trees, the waters, the mountains, the desert, the valleys, we all want to preserve and protect this place we call California and home to so many, let’s first acknowledge whose lands that we’re on.

ALEXIS: So if somebody wants to make a land acknowledgement in other cities or regions of California, what are the best ways for them to proceed? Are there resources available to help guide them?

JOELY: Well, we have a great resource for folks at our website. It’s a 20-plus page, easy-to-read document that lays out the who, what, why and where of land acknowledgments. And for people who are trying to determine whose land they’re on, there are websites where they can just type in their zip code for an answer. Organizations can also download our toolkit, which gives some really helpful tips.

We don’t recommend that they stop there. We recommend that they reach out. You can call us at the California Indian Culture and Sovereignty Center, or the California Indian Museum and Culture Center in Santa Rosa. We’ll be happy to help them and connect them. But most importantly, we want people to develop relationships with the tribal peoples in their region. So it’s not just, “who do I need to call to get the statement?” It’s building upon that relationship.

I’m also a big fan of posting a land acknowledgement in a permanent place. Whether it’s on your website or on your wall, as you’re hosting an event or inviting people in, ask them to recite it publicly. There’s power in oratory, and I know it makes me feel good to hear others recite it.

ALEXIS: Thank you. This might be a new idea to some people now, but as people continue to learn about the true history of California and the U.S. as a whole, I think Indigenous descendants everywhere will be proud to state their ancestry. I want to see this bill get passed, and I believe we will. Thank you so much for your hard work on this.

JOELY: Thank you, Alexis. Hopefully we’ll be celebrating the passage of this bill sometime in the near future.

Update: On June 8, the Tribal Land Acknowledgement Act of 2021 (AB 1968) passed the California Assembly by an unanimous 76-0 vote. The Tribal Land Acknowledgment Act legislation was referred to the Senate Committee on Natural Resources and Water and is awaiting review. The California State Legislature reconvenes from Summer Recess on July 13th [Source: Native News Online, July 1, 2020].