The Ojai Foundation in Ojai, California, is a 42-year-old retreat center whose mission is to “foster practices that awaken connection with self, others, and the natural world.” The new co-directors, Sharon Shay Sloan and her husband Brendan Clarke, were invited to lead a transformation of the Foundation. But disaster hit just weeks after they arrived. The Thomas Fire — one of the worst in California’s history — blazed through the education center’s 37 acres and destroyed 80% of its buildings.

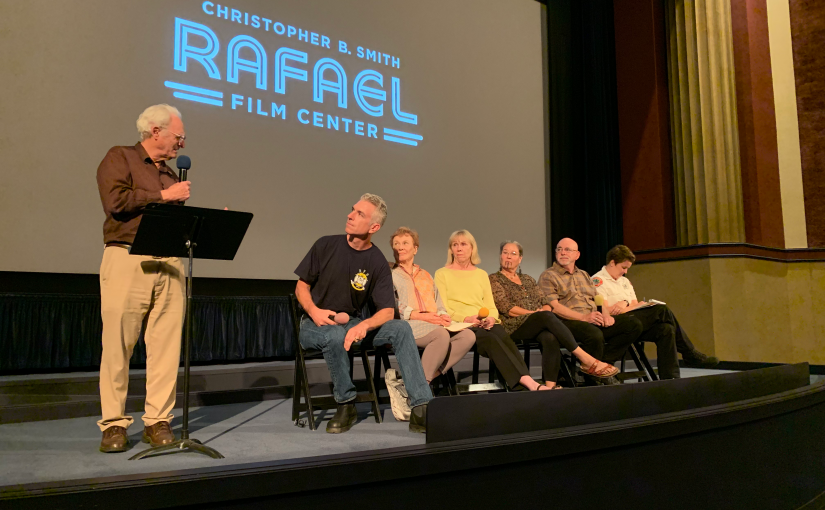

Arty Mangan, Director of the Bioneers Restorative Food Systems program, interviewed Sharon about the aftermath of the fire and how she’s leading the effort to rebuild Ojai from the ashes. This story holds deep lessons on being resilient in times of disaster. Shay will be facilitating Prayer and Action Talking Circles at the upcoming Bioneers Conference.

ARTY MANGAN: Shortly after you left Sonoma County in 2017 – right after the Tubbs Fire had devastated Santa Rosa – and moved to Ojai to co-direct The Ojai Foundation, you experienced one of the largest wildfires in California history. How did you get through that?

SHAY SLOAN: We got a call within the first hour or two of the fire starting. At that point, it was a small neighborhood fire. It didn’t have a name yet. A dear friend and colleague got word from a neighbor, and he let us know. We went up to a ridge and as far in the distance as we could see, there was the fire. It was a freezing cold night with 80 mile-an-hour wind gusts. So, it was already very extreme. Even though the fire was very far away, we immediately felt a sense of the power of the moment.

It’s an east-west valley. On the southern half of the horizon, a red puff of smoke completely covered the hills and the sky, and the northern half of the valley was a crystal clear, star-filled, full-moon, bright night. It was gorgeous, the world as it was made. And on the southern side, the world that the humans made and how that interacts with natural forces. There was this visual visceral imprint that came through watching the fire move through the landscape.

I take that much time to describe the moment because in large part that was what sustained us. We had literally seen the coming of something, the arrival of something, the energy and the strength, the potential, and amidst that, the backdrop of what was happening on the CB radio and the news.

There was little coherence in the wider social fabric, immediate overwhelm, and a sense of near-panic already in the air that was apparent from the first moment of the fire.

So many people have pointed toward this time, toward the coming changes whether it’s climate change or social uprisings, whether it’s through prophecy or science. I would say that I have been preparing for these times and have been privileged to hear the stories and learn from many people who motivated me to prepare, to the best of my ability, both in relationships and in practices.

There was the seeing and perception through direct experience, and then there was the being held by relationships by people who were not in the same immediate crisis, but who were aware of and caring about our experience, on a personal level and for The Ojai Foundation itself, as well as the wider community.

Then there are the practices. What do you do day-to-day when there’s so much stress running through your body? The people around you are moving in and out of panic. The emergency services, the county, the state, were completely in over their heads. So, we rely on the inner, the relational, and the spiritual.

ARTY: That was really beautiful and powerful and devastating to hear. Once the fire had gone through and done damage and changed lives, did you experience post-traumatic stress syndrome?

SHAY: Honestly, I felt, for the most part, that we were able to keep pace with the changes in a way that we weren’t accumulating trauma. We were watching and studying all the maps. We had to get around the police barricade. We lived through the intensity of the experience. We were the first ones on-site to walk the full land and take in what had been burned and what hadn’t burned. We were still putting out fires while we were there. We were very much on the frontline of that experience.

We did accumulate stress from the administrative challenges of life. When you lose almost everything that you have, there’s so much to deal with. We suffered that loss on a personal level. And The Ojai Foundation lost 80 percent of all structures; all of the residents and all of the staff lost homes. We couldn’t operate the business. We lost all of our tools. It was a complete devastation, and yet there was something about the resting into what I named previously that I feel really gave us a minimal accumulation of traumatic residue.

But the way that I am able to recognize that we did have some trauma is that even to this day, we will barely buy anything. There’s a feeling that it could all go. Knowing impermanence is part of it, and not wanting to hold onto anything because it could be lost again. But there’s another part, which is we also felt what it was like to not have stuff. I left with a suitcase and a duffel bag. There was a lightness to being that was very freeing. There wasn’t only loss, there were gifts. I think so much of the story that gets told is about the devastation, the trauma, loss, and the horror, and all of that is true. I can say yes, I lived all of those things, and I don’t carry around so many things with me anymore. Many of them, I didn’t actually need.

So, there’s a lot of mixed experience. And I feel we’ve been able to have both the gift and the losses of that time.

ARTY: How did that experience change the way you understand or embody emotional and spiritual resilience?

SHAY: Resilience is often talked about on an individual level. Do we have the capacity to regenerate and continue to harness our energy and bring our gifts to the world through challenging times? I rest my weight in that, but I also rest weight much more deeply in community resilience, not just local community but also interwoven communities. The experience that we had of people from literally all over the world writing, sending letters, sending funds to The Ojai Foundation, sending gifts of clothes to me and Brendan. There was so much outpouring of support that made our resilience possible.

We extend our wellness and resilience to each other in times of need, and that allows for the buoyancy, for the uplifting of one another through a time when otherwise we could buckle under the pressures of our own circumstance.

The need of relationship, not only for networking on a superficial level, but developing networks of committed relationships, is what gave rise to the Fire Fellowship. This is one of the programs that we have launched at The Ojai Foundation since the Thomas Fire, and so far have been able to continue it through the time of the pandemic. Part of our intention is to support the Fellows to develop a network of resilience and support, as well as to gift the practices that helped us to go through that process, combined with other practices that the fellows themselves are carrying.

ARTY: In our previous conversation, you said: “What do I need and what can I offer? How did that guide you and how did it express itself?

SHAY: There’s a saying from Christina Baldwin: “Ask for what you need, offer what you can.” That has definitely been helpful guidance, both since the fire, as well as in life in general. I find this is increasingly important the stronger our need becomes, whether it’s a need for love, or need for shelter, or need for money, or friendship. Needs come on so many different levels. The more that we focus solely on the need, the more we create the conditions where that need cannot be fulfilled. If someone is feeling a poverty of the spirit, if they focus on what they have to offer, what are their gifts – no matter if it’s a penny, an hour of time, an ability to grow food or whatever the gifts are – there’s a way where we restart the cycle of reciprocity in our own hearts and minds again. Through that reciprocity, I find both resilience as well as strength and stronger relationships.

It’s never just I need something from you, but I have a need and here’s what I have to offer. It’s become a bit of a mantra for my life. It saved my butt time and again in my marriage. If I get really into that indignant position of: I need this thing; I need it. That other person can become so resistant to that kind of demand, but if I can center on what do I have to give, what do I have to offer, and I have a need you can help with, it’s received so much better.

ARTY: That’s really impressive and uplifting. But I also want to ask you: In your darkest moments, what do you fear?

SHAY: Years ago, when I was contemplating if I wanted to be a mother? Is that part of my path? I found myself in a very, very deep conundrum, and I wasn’t able to put words to what I was feeling. At a certain point, I found some of the feelings that were underneath, and I cried and I cried and I cried. What I realized was that I will not be able to protect a child. There’s only so much I can do to protect them from the conditions, from the society, from the violence, from the fires, from all of those kinds of things. I am coping with the limit of my ability to protect that which I love – my child, a wilderness area that shaped me, peoples who live on the front lines. There are so many aspects of my life where I have come to understand the helplessness that I feel when faced with the scale of what we can actually protect. So, the deeper fear underneath is no, we can’t.

We’ve seen that time and time again. We couldn’t stop the fire from taking our home or The Ojai Foundation. There are many things that have been lost and destroyed from species to people who we love who have been lost to disease or suicide. It’s the reckoning with that. It’s not so much a fear, but a reckoning with reality or potential reality.

ARTY: What do you want to instill in your 18-month-old son about how to face a future that in all likelihood will be more unstable and dangerous than even the world we live in today?

SHAY: I take refuge in believing that he’s made for these times. The young people today are coming into a time of such deep initiation through transformation of the culture and transformation of the environment that for him and other people it is the fabric that they’re growing up in. It’s not like life was something and then it becomes something else. This is his life from day one.

The more that I can lean into seeing the world through his eyes and understand the innate capacities that he and other young people are coming in with, the more I can and learn from them and nurture those strengths.

I can show him how to lean into networks of support, resources and practices. My husband is mixed race, and so my son is mixed race. I feel we have a very deep responsibility for his education on anti-racism. They say that by age 2 or 3, babies start to internalize racist ideas and beliefs and start to sort the world through what they’re seeing and experiencing in the culture, in the books, in the media, etc. So how do we maintain and create an anti-racist education for him from day one so that by the time he is 2 or 3, which is coming for him in the next 6 months to a year and a half, he is already internalizing an anti-racist view and way of life.

It’s a job I take very seriously. I’m very grateful for the people and practices, and all of the work that has been done already in these ways. For young people who are awakened and good people who are here to support the youth in building those intergenerational relationships, I take refuge in all of those things, certainly on a more personal level and in a different way than I did before I was a mother.

ARTY: After the rebuilding from the fire, what are some of the aspirations and challenges for The Ojai Foundation?

SHAY: It’s been a long road. We did an extended period we called the Recover and Reimagine phase. Many people asked, “When are you going to rebuild and put it back the way it was?” But it was very clear to us that there was no going back, that things had changed at a scale and in such a way that we could only go forward. So, we put our daily attention toward recovering basic infrastructure and basic safety on the land. Whether it was from tree work or repairing electrical or water damage, or damage to buildings or simply moving debris. We also turned our attention toward reimagining how to be with the landscape, how to be with the organization, and with the community and the work.

In going through that process, a wonderful man, Andy Lipkis, founder of Tree People, who’s a long-time friend and colleague, came and walked the land, and he said, “Everything must teach. Everything you do through this recover process has to teach what’s possible.” That really resonated for us, and it’s part of why we knew there was no going back. We weren’t going to put buildings back on the periphery of the ridge in a place where we knew fire would come and ravage them again in a similar way. We had lived through climate disaster and we learned the lessons of what that means in that landscape.

There was a very strong lesson around the relationship of earth and fire. So, we have only rebuilt two things, a round, earthen meeting building that’s 80 percent done and an earthen tool wall to store all of our garden tools. Other than that, we’ve just restored the land and the infrastructure.

Our approach to the land itself is to model climate resilient design and stewardship of the land. That will be a slow process of continuing along the lines that I’ve named and moving at a pace good for the land. The land is still in deep recovery. If you dig down anywhere on the land, you still find ash. That ash is like medicine containing minerals and other gifts to regenerate the soil. So, it’s a slow build. And we’ve prepared the land for camping and day use, but we will not be building back the larger structures quickly.

On the level of reimagining programs and the organization, The Ojai Foundation is 45 years old, and there are so many teachers and people who have come through. The practices and ways of being and doing have gifted thousands and thousands of people. I don’t really know the numbers, but I would guess over a hundred thousand people have had direct and transformational experience on that land or with our practices. We’re now in 2020, so if we were going to start with something new, would we start with what was happening in the 1970s or anything in the past? No. Because we’re in different times. This time has given us very, very deep pause to ask how do we go forward? What does the leadership look like? Do we carry on the same practices? How do we continue to evolve?

We are pausing many of the programs and asking for an evolution. We were planning to reopen in March, and literally the week before that reopening, the global Coronavirus pandemic erupted. So, our closure has been extended because of the pandemic.

We find ourselves again in a perpetual closure of the land base, certainly through 2020. We don’t know what will happen going forward. The combination of these things got us into a very deep contemplation of potentially closing the land base, potentially closing the organization, looking at how to go forward and asking if it might it be time for a complete change of form.

After a three-month listening period in which we considered whether it’s time for a complete change of form or not, the comments from the board will be sent out to 270 of The Ojai Foundation’s closest allies. It basically says that while we thought we were turning toward a rapid change of form and potentially leaving the land base, what we have learned from this time of deep listening and meeting with the community and stakeholders is that there is still important work to do in the name of The Ojai Foundation and in the land sanctuary that we steward. That work has to do with increasing multi-cultural leadership in the organization and a much further evolution of the practices. It has to do with looking squarely at issues of power, equity and access, both within The Foundation and in the broader community connected to it. Now is a time to ask what gifts have been received and given through the work of The Ojai Foundation? From where have they been received, and to whom have they been given? What harm has been caused alongside the gifts? Who has been missing or excluded from the conversations, practices, and leadership? As we honor what has been, we also recognize that for our organization to remain visionary, we must continue to evolve our forms, our practices, our conversations and our relationships.

That’s what is immediately ahead for us, and we’ll see how it continues to unfold. It’s been a big three months; to be honest, I think in some ways it’s been harder than the fire because for this process we have to choose everything. With the fire, we were responding to what happened, but this requires another kind of decision, one that means walking consciously toward transformation. That is a whole other human capacity, and one that we all carry. If every organization, nation, business, marriage, and individual contemplated completely changing the form and deeply engaged that potential, I am curious what new possibilities would arise in the wake of the old. What world would start to become possible?