Kandi Mosset is a mother and member of the Mandan Hidatsa Arikara nation of North Dakota. She is known worldwide for her involvement on the frontlines of the protests at Standing Rock.

With a Masters in Environmental Management, Mosset joined the Bioneers Indigenous Forum in 2014. Joined by fellow water protectors, Mosset returned to the 2016 Bioneers Conference to provide an update on Standing Rock that reached millions. She currently works with the Indigenous Environmental Network (IEN) as Lead Organizer of the Extreme Energy and Just Transition Campaign, and she previously served as the IEN’s Tribal Campus Climate Challenge Coordinator.

Mosset is passionate about bringing visibility to the impacts of climate change and environmental injustice, specifically those affecting Indigenous communities throughout the world.

Bioneers was thrilled to have Kandi Mosset return for the 2017 conference. Below is the video and transcript of her keynote speech on defending indigenous lands and communities from the negative impacts of the fossil fuel industry.

Kandi Mossett:

The Mandan Hidatsa Arikara nation is in North Dakota, which is made of three separate and distinct tribes that were put together on the same reservation in 1860 by this federal government, because we were similar enough, and because many of us were decimated by smallpox that we were really small in numbers by the time that happened. But we have our separate languages and cultures and traditions.

We’re earth-lodge dwelling tribes. It’s not like the Western movies where you see teepees and horses and buffalo and that’s it. We had those things for sure, but we were farming tribes. We grew corn, squash, beans, tobacco, and as such always lived along the waterways and the bottom lands of the Missouri River for a really, really, really long time.

One of the first threats after the reservation in 1860 was something called the Flood Control Act of 1944, also known as the Pick Sloan Act, where they came up with the brilliant idea to build this series of dams along the Missouri River. Incidentally, every single one is below a reservation — flooded us, and that dam, the Garrison Dam, created our reservoir of Lake Sakakawea, which we have come to embrace as our waterway, as our life blood, but we also had a moment where we were forced into a cash economy as a result.

My grandma says it’s like we were forced through a door and could never look back again. We had to go to the toplands because that dam flooded all of our Class 1 and Class 2 agricultural lands on the bottom lands, and all of the towns and villages that we had to come to accept, that were forced upon us by the federal government.

When our chairman, at the time, George Gillette, signed onto that deal, he cried because they were already $60 million into building the project by the time we “agreed” to do it.

So then North Dakota was like, “Oh, well we have this lignite coal here. It’s a beautiful thing.” But it’s not. Lignite coal is the dirtiest coal that you could possibly imagine that comes from North Dakota. Seven coal-fired power plants, several mines that we have impacting our air. That has been happening for a very long time.

I remember going to the coal plants in seventh grade. Our whole class fit into the back of a shovel, one shovel that they used to dig it up. And they were telling us about how great it was. How we could get jobs in the coal industry, and it was going to be a wonderful thing. I remember, I was like: I’m too cool to wear these goggles that they gave us, so I took them off, and I was like, Oh crap, there’s all these particles going into my eyes. So I put them back on.

But they didn’t tell us about what it was doing to our watersheds. They didn’t tell us that every single bit of our over 11,000 miles of rivers, lakes, and streams in North Dakota would eventually be contaminated with mercury as a result of that industry. That is before the fracking you may have heard of. This is all before we have the nation’s only commercial scale coal gasification plant. We have uranium mining. We have over 8,000 acres of underground nuclear warheads stored in North Dakota. Okay? And then enter fracking and the Bakken shale formation that exists where I’m from.

They call my reservation the sweet spot because at least one-fifth of the oil that comes out of there comes from under our feet. So instead of seeing fields, we started seeing these popping up all over the place. Rigs everywhere. On my reservation there’s no setbacks. Zero. They’re right behind apartment buildings where children ride their bikes and play. So we see these things that say for sale, industrial zoned, leased to the industry.

North Dakota is full of sunflowers, as my daughter is showing you here. We have wheat, canola, corn, barley, oats. We’re known as the breadbasket of the country. And yet, this is what the wheat fields are starting to look like. This one was four years ago, and it’s still not cleaned up because this spill was so toxic in this wheat field, which this farming family hopes to be able to put into production again.

We started seeing truck traffic coming into my community and just tearing up our roads. Roads that actually used to be roads are now just gravel. And nobody is fixing them. State of North Dakota’s not because we’re sovereign nations.

These trucks take liberties. They fill up their frack trucks with pristine water where our families used to fill up their cisterns, families that have to haul water. So the next person that comes along has no idea whatever flow back was in that truck.

This is Main Street, Newtown, North Dakota, little tiny town where I grew up – 1,500 people in my community until the oil boom. Boom, all of a sudden 5,000 people, probably three times as many trucks. They dump those frack fluids — toxic, never again used for human, animal, any consumption — right onto the roads because they can get away with it in Indian country. Whenever there’s an accident, traffic gets backed up for miles and miles, and hopefully people aren’t hurt. But sometimes…

This is my uncle’s truck. He was moving my cousin. Him and my brother were riding. A semi decided they were going to take over the whole road, and they either had to hit the ditch or have a head-on collision with a semi. They hit the ditch and they were okay. They had cuts, bruises, scrapes. Not everybody is always so lucky.

In 2008, when I really started fighting back against this industry it was because I had a friend who was killed by those semis, and she was 23 years old. Literally crushing her. Nothing was ever done. Since that time over 40 people in my community have died just running on the road, taking their kids to school.

That is some of the social. What about environmental?

This spill in 2014 still hasn’t been cleaned up. We live in the Badlands of North Dakota. It’s not all flat, like some people might think. We have beautiful areas called the Badlands, and they tell us time and again that it’s not getting into the water when spills happen. Don’t worry about that frack water. When it touches stuff, it’s not that toxic. They said — the EPA and others — that this is clean. There’s still heavy mercury, heavy metals, heavy toxins, arsenic sitting on top of this soil, from 2014, and it’s “cleaned up.” They tell us don’t worry when there’s a spill because we’re going to have these sand bags here that are going to take care of everything. It’s not going to get into Lake Sakakawea.

Well, this was taken out of Lake Sakakawea when my sister was swimming. This water came out of the lake, so I took it to the North Dakota State Health Department, charged $200 out of my own pocket to see what the heck this was. They’re like, “Oh, don’t worry. It’s a blue-green algae bloom.” I was like, “Okay. What does that mean?”

It’s toxic. You’re not supposed to be swimming in it. You’re not supposed to drink it. This was taken one mile from the water intake plant for our community.

In addition to the water, our air is being polluted. How many have you been to North Dakota? Raise your hands. How many big, huge cities like New York have you seen in North Dakota? None. Because there aren’t any.

This circle you’re looking at is not from the lights like you see in the eastern part of the country. It’s from the flares. You can literally stand in one area and do a 360 and feel like you’re in a war zone. I can’t tell you how hard it is to be home with my daughter in the back seat, and I don’t even want us to have to breathe, but we don’t have a choice. So we thought.

We’re going to fight back against this industry because look at this…Just a few years ago, you could see for miles and see the buttes, all of the compounds that are in there. All I wanted you to notice about this was where the little red arrows are because those are carcinogenic, which means cancer-causing. As a cancer survivor, who shouldn’t be standing here today because I was diagnosed with a Stage IV sarcoma tumor when I was 20 years old, this is really triggering to me. And this is just 652 of the 2,000 possible chemicals that can be in that frack water, and every single one of those is of concern.

They don’t care where they put these things. My grandmother used to fast here. She used to go out and collect juneberries, ground-berries, chokecherries, turnips, and now signs say, do not enter; you cannot be here.

And then came the man camps. Did you know that in the past nine months alone there were close to 100 people rescued from the sex trafficking industry, the youngest one was 3 months old?

Crime came with the industry. It’s inevitable. These are just headlines I took from my local papers that you’re not going to see in mainstream media. Every single one of these has a story. I don’t have enough time to share with you today. But imagine, the worst thing that used to happen when I was little was that the bad kids — us — used to egg our teachers’ houses on Halloween. That was the crime in our community. And now this.

With that came drugs, came heroin, something we never had in our community before, and when people got addicted to heroin, the industry, the police, “Oh, they’re just druggies.” There were no services for the people.

So when people like Ashley got addicted to heroin there was nowhere for her to turn. She laid in a hospital bed for three days while her hands and her feet turned black, while her internal organs shut down before she died at 28. In the last year we buried Lisa, same thing. No one to turn to because she was just a druggy. No, she was a person that left behind five children.

My cousin Daniel went missing in 2013. We knew that he was with MS-13, a known organized crime gang, that originated out of Venezuela. We knew the night he went missing, he was with those kind of people. We searched and searched for Daniel for months, and we found him — in Lake Sakakawea, under the bridge. And because of there were no stab wounds, there were no gunshot wounds, it was open and shut. We never knew, and we’ll probably never know who killed Daniel. And that happens all the time as a result of the oil industry.

And what do we get? What’s our thanks for allowing these people to come into our communities? Written on our dumpsters for our kids to find? Racism, as if it’s our fault that they’re there.

We fought against the semis. We fought against the trains. Because then that bright idea was to bring these bomb trains and send them out all over the country. And it hurt every time one of those blew up, because they came from my community. In Canada, 47 people were killed, including two kids under the age of 5 when ones of these trains blew up. Then, what was the next brainchild? Pipelines.

You’ve probably heard of the Dakota Access Pipeline. You might know how it ended at the time. Yeah, we were forced out by gunpoint from our US military for trying to protect our water. When we say the frontlines, people get triggered because they say, “Oh, that connotes war.” Well, if you don’t think we’re at war then you’re sorely mistaken and you need to wake up, because we are on the frontlines.

We stood there with our sage and our sweetgrass and our medicine against armed military — to protect water and tell people water is life. It doesn’t matter that the camp was physically forced out because they can never take away the fires that are burning in our hearts from that, and we’re never going to quit. We are going to continue to fight, because it’s not just about one pipeline.

Raise your hand if you heard of Dakota Access. Okay, now, raise your hand if you heard of Sakakawea Pipeline. Hmm…That one quietly went under the water at the same time. You see, it’s not just about the symptoms. It’s about stopping it at the source. And I want to show this video of what we’re continuing to do at home.

So 3 years ago that we have have gotten our Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara nations elders and representatives together in 20 years, to work together and do a water blessing.

You know, these industries, they won’t return here, they are only here for the money, they want to extract as fast as they can.

We have a lot that is at stake here, there’s a big battle going on right now and we’re in the battlefield.

What we’re doing here is bringing folks from all over the United States and making sure that people understand that the legacy here, the legacy of extraction, ultimately goes downstream towards other communities in the United States, especially in the South.

So making those connections from the extraction point through the pipelines, you know, all the processinging and refinement, and how we’re all in this struggle together. I think it’s just really important to bring people together and understand we’re not alone when it comes to these extractive industries and how they’re impacting us. And the whole message of the day is, “Just keep it in the ground. Stop it at the source.” Then, all of the negative symptoms that negatively impact everybody else won’t have to happen.

Right? It seems like common sense to me. Just because you don’t see us in the media fighting at Standing Rock doesn’t mean we went away, or that we’re not going to continue to fight in the Bakken. You can bet that we’re in our communities fighting and pushing back.

We’re making those truck drivers feel uncomfortable when we put our up signs telling them that we don’t want them there. We’re going to continue to bring people to North Dakota and have these toxic tours, just like the one we just had this past August to show that the symptom — the pipeline is still there — but we’re going to fight to stop it there, because fracking is a problem in this country. It’s also a problem worldwide, and that’s just one of the problems of the fossil fuel industry that threatens life.

Mni Wiconi is so much more than just a slogan or a saying. Water of life is literally when we’re pregnant, we carry our babies in that water. In that moment, that moment when you understand what that means is so powerful. And I like to share it with people. Because we have a responsibility to protect that life, to show them that they can be the future power shifters, and to get them ready to do it because these things take a really long time. But we’re strong and we’re smart, and we know that we can do things like decolonize our own minds. Yes, you can.

Look up Dr. Michael Yellow Bird. I don’t have time to go into the whole thing right now, but neurodecolonization through mindfulness, you watch one of his things, pow! Yeah, it’s amazing. That’s what we can do as individuals if we want to right the wrongs in the world.

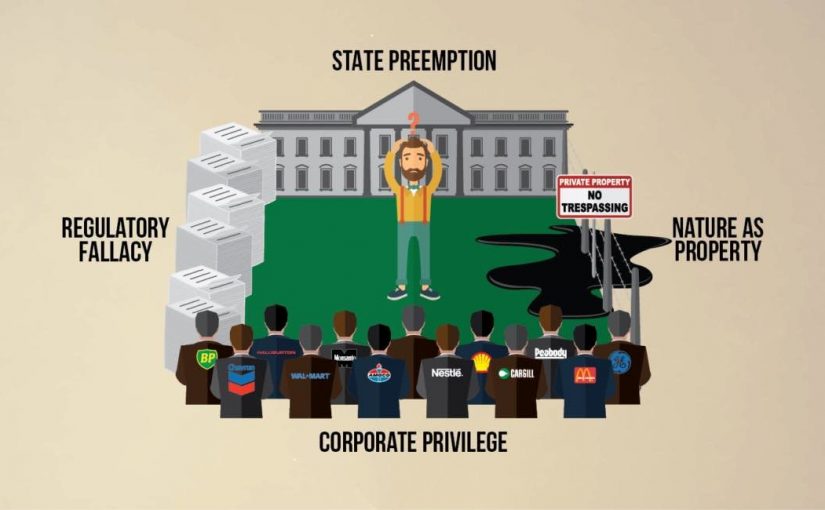

Sure, renewable energy is great. It is good to have those things. It is good to transition. But that’s not what’s going to save us. We have to get to the very heart of the problem, of this broken system, which is capitalism and colonization. We need to do it and we can.

You can get the book if you’re not indigenous. I don’t know how much sense it’ll make, but it’s pretty good. It explains what that means. Don’t be afraid of decolonization. It can be as simple as planting a garden, honestly. Start there.

Our little kids, our children should be allowed to continue our culture and practice our way of life.

This is one of our Earth Lodges in a modern-day spin that we’re building in our community right now. Because our country, our world, is addicted to oil. We have to admit it. We have to admit the foundation that we’re built on is a bad foundation, and it has to crumble so that we can rebuild it.

If we have to go to DC and leave our communities and march and say, “Hey, No. 45, you’re insane, and we’re going to do everything we can to get you out,” then we will! Yes! Don’t be afraid. Don’t be afraid and don’t sit on your couch and wait for somebody else to decolonize your own mind because you’re the only one that can decolonize your own mind. I’m sorry. But you have to do some homework.

Please support the Dakota Resource Council, who supports our local Ft. Berthold power group. Please don’t forget about the people on the ground. Dakota Resource Council is in North Dakota trying to do good things, and they need support. And please support us at the Indigenous Environmental Network because it’s for the next seven generations.

If not us, who? If not now, when? We can do this, people. We can do it together.

It has been a wonderful fall in the Rockies, with cottonwoods and aspens more brilliant than I’ve seen them in years. When you duck into the groves, the air itself is golden. Quaking aspen has a great name: Populus tremuloides. It describes on the tongue what the aspen does, which is to tremble in the slightest breeze, with a sound like bones rattling.

It has been a wonderful fall in the Rockies, with cottonwoods and aspens more brilliant than I’ve seen them in years. When you duck into the groves, the air itself is golden. Quaking aspen has a great name: Populus tremuloides. It describes on the tongue what the aspen does, which is to tremble in the slightest breeze, with a sound like bones rattling.