This article was authored by Mark Trahant and originally published at Indian Country Today. Read the original here.

The list goes on and on: The pandemic. George Floyd’s murder and the growing call for racial justice. Pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong, and, at the same time, an orchestrated attempt to overturn a democratic election. Global protests over vaccines and masks. And now war. How does this make any sense?

“Could there be a symbiotic relationship between COVID-19 and conflict?” ask scholars Alexi Gugushvilil and Martin McKee. In a paper written in October 2020 for the Scandinavian Journal of Public Health.

“At the beginning of the pandemic, UN Secretary-General António Guterres appealed for an immediate global ceasefire to enable the world to confront ‘a common enemy’ but his plea went largely unheeded,” the scholars wrote. “We argue that there is a bidirectional relationship between COVID-19 and conflicts: on the one hand, circumstances associated with wars may facilitate pandemic spread; on the other hand, COVID-19 has already heightened xenophobia and nationalism, which in turn can encourage armed confrontations.”

Gugushvilli is an associate professor of sociology at the University of Oslo. McKee is professor of European Public Health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. He is also past president of The European Public Health Association and a health policy expert on the former Soviet Union.

“Wars and epidemics have a long and close history, going back at least to the well-documented Plague of Athens in the 5th century BCE,” the scholars wrote. And a common thread is when the national economies are shrinking.

The link between war and plague is also a familiar story in Indigenous communities. Europeans brought with them dozens of infectious diseases along with their weapons of war. Smallpox, chickenpox, cholera and even, the common cold.

There is also a relationship between mass protests over such things as mask requirements and war. There were more than 139,000 recorded protests in 2020, an increase of 68.5 percent from the previous year. More than 33,000 of those protests were directly related to COVID-19 and responses to the pandemic such as the trucker blockade in Canada and the convoy of trucks now headed to Washington, D.C.

“These protests are an obvious marker of public discontent that can easily be exploited by powerful forces. here, history again offers a warning,” the scholars wrote. “Those German municipalities that suffered most in the 1918 influenza outbreak were the ones that saw the greatest electoral gains for the Nazi Party a decade later.”

So what now? Will history repeat or even, as some say, rhyme? That question depends on the policy choices that are ahead.

The Economist says: “Over the past decade, intensifying geopolitical risk has become a feature of world politics, yet the world economy and financial markets have shrugged it off … Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is likely to break this pattern, because it will result in the isolation of the world’s 11th-largest economy and one of its largest commodity producers.”

That means higher oil and gas prices because Russia is one the world’s largest producers, and it dominates the European market for natural gas. On Thursday the price of oil topped $100 a barrel (a cost that will soon show up at gas stations) and Germany said it would no longer permit a pipeline project that is supposed to transport natural gas from Russia to Europe.

And while it’s true that Russia views NATO as a threat; this invasion is also about natural resources, climate change, and shrinking economies.

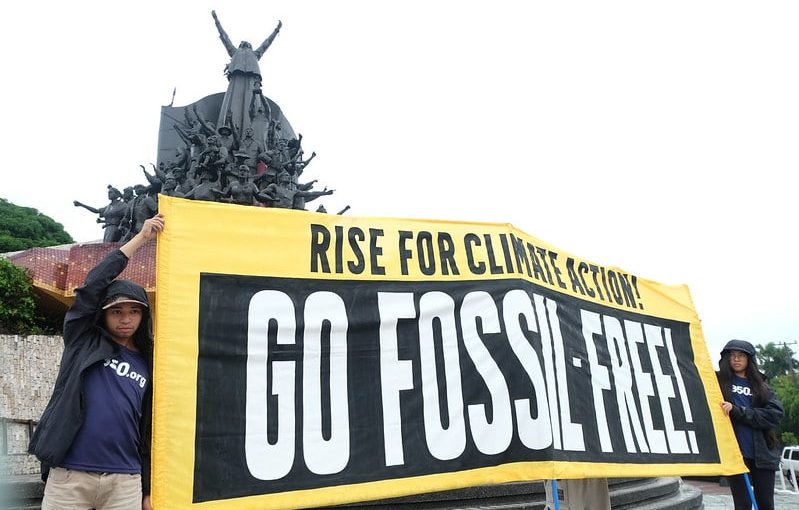

“First, we know that it is only because of oil and gas that Russia is able to afford this military invasion,” said Jade Begay, climate justice campaign director for NDN Collective. “This makes it clear that not only are oil and gas used to carry out war but are also a root cause for exponential climate change. Second, as an organizer who is actively working to shut down fossil fuel infrastructure, I am hyper aware that this conflict will potentially drive up domestic oil and gas development, onshore and offshore gas leasing, and/or potentially roll back recent wins when it comes to fossil fuels, thus contributing to an increase in carbon emissions. Finally, I’d be remiss to not mention the impact that militaries have on the climate, when it comes to the U.S., our military is the single largest institutional polluter in the world, which creates more greenhouse emissions than 140 other countries.”

The Economist predicted that Russia may deliberately create bottlenecks in order to raise prices.

Normally governments go out of their way to limit the impact of war (or any other disaster) on the price at the pump. Governments do not want people mad at them over higher prices. But what if this time is different? What if this is a proxy war for oil?

President Joe Biden has talked about climate change as an existential threat. So perhaps the smart play is to lean into the price increases and cut off Russia’s ability to market oil and gas.

As the president said after the invasion: “President Putin has provided the world with an overwhelming incentive to move away from Russian gas and to other forms of energy.”

Some fear that the White House won’t make the hard call.

“First and foremost, our organization, the Indigenous Environmental Network, stands against any and all forms of imperialist expansionism, which we’re seeing right now with Russia invading Ukraine. But we also saw that when they already invaded and annexed Crimea, which impacted Indigenous communities who live in Crimea, and now we’re seeing potential violations of human rights in Ukraine at this very moment,” said Dallas Goldtooth from the network. “It has to be stated that almost any and all conflicts in the world today implicate fossil fuels. Russia is the second largest producer of natural gas in the world behind the United States. And is the top supplier of gas to Europe. Our fear is that this conflict will only deepen the pockets of the oil and gas industry as any modern war does, but more, it will give the Biden administration further reason to delay action, to stop the expansion of fossil fuels here in the United States.”

But there is another alternative.

Begay is Diné and Tesuque Pueblo of New Mexico. “Over the last month,” she said, “fossil fuels have been at the center of how nations are holding leverage against one another, point and case, the Nord Stream 2 Pipeline. This should be a clear signal to our leaders that we need a Just Transition & Green New Deal now, so that we are liberated from this toxic dependency on oil & gas.”

“This is a moment to seize on the call and demand for a just transition away from fossil fuels,” Goldtooth said. Too often the conflict over fossil fuels come at the detriment of Black, Brown, Indigenous and working class peoples. “Here’s a moment for us to step up to the plate and say, ‘Hey, we’re not gonna be feeding the beast anymore. We’re gonna stop the exports of oil and gas.’ We can take an opportunity to set the path forward because the U.S. is the largest provider of natural gas on the planet. They can take, make a solid step in the right direction by stopping the expansion of that sector and investing in communities for a just transition.”

A Russian-controlled Ukraine could add to the global warming matrix because it could expand oil and gas as well as uranium and other minerals that can be mined.

Then again Europe might be ready for a different energy.

“There’s this narrative, this false narrative out there, that to step away from fossil fuels is impossible,” he said. Goldtooth is Mdewakanton Dakota and Dine. “Countries are already doing it. Iceland’s a great example. It’s getting the vast majority of its energy from renewable sources. On a smaller scale, tribal nations and small communities are already set in the path forward on how to step away from oil and gas.

And so we just need to continue to invest in those local visions of how we wanna make a better future for our communities, for our people and for the ecosystems around us. So that the path forward is out there, we’re just not elevating those uplifting those stories.”